Saturday, December 07, 2013

Running Out of Karma: Tsui Hark's Working Class

Running Out of Karma is my on-going series on Johnnie To and Hong Kong cinema. Here is an index

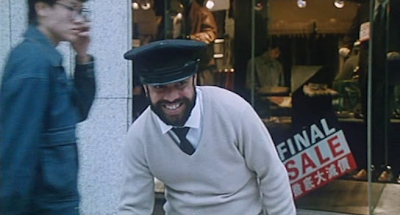

A Cinema City film in all but name, as Tsui Hark directs for his own production company, Film Workshop, this comedy with pop star Sam Hui (of the Hui Brothers and Aces Go Places) and rock star Teddy Robin (of Tsui's own All the Wrong Clues. Tsui himself rounds out the trio of workers trying to get by in the world of benevolent old owners and evil middle managers (none other than Ng Man Tat - it's going to be weird seeing him as Stephen Chow's sidekick again after he's so great in these 80s villain roles (A Better Tomorrow II, My Heart is that Eternal Rose)). The three work in an instant noodle factory (is there a Cantonese word for 'ramen'?) and play a variety of pranks to undermine the bosses. Much to the irritation of Tsui's wife (Leung Wan-yui), Tsui brings the homeless Teddy home to live with them. Tsui and Teddy make a great comic pair: tall and thin with, as Bordwell puts it "an intimidating goatee" and short and squat and almost always wearing sunglasses. Sam falls in love with the boss's daughter, Joey Wang, but she hides the fact that she's rich from him (Sam wonders why a fancy Rolls Royce is always following them everywhere they go on their neon-lit dates through the city at night). Then everyone plays soccer and everyone cheats.

Rather than grafting a Socially Important Message onto an essentially silly comedy (the example that comes to mind is Eddie Murphy's The Distinguished Gentleman, one of the worst movies I've ever seen), Tsui comes at it from the other direction. He takes what could be, in less interesting hands, a serious scenario about worker exploitation and the lives of the poor in a booming economy where the rich keep getting richer and makes a farce of it. The humor comes organically out of the heroes' anarchic rejection of the social codes that enforce fealty to the bosses, no matter how treacherous they are. Every prank becomes an act of protest. Even the love story plays backwards: it is Joey's superfluous wealthiness that is shameful, not the tiny apartment Sam shares with his mother. The politics isn't the least bit profound, but it is a little revolutionary.

I was disappointed that Tsui's breakthrough hit All the Wrong Clues (...For the Right Solution), lacked the oppositional elements that made his first three films so exciting, opting instead for pure farce and parody. His entry in the Aces Go Places series followed in that vein, privileging goofy special effects over not only politics but quality stunt construction (I much preferred the second film in that series, directed by Eric Tsang). Working Class I think gets closer to the heart of what makes Tsui a great filmmaker: the mixing of New Wave politics with popular genre filmmaking. It's not the commodification or assimilation of leftist ideals into a corporate mainstream, but the repackaging of them as a shiny, goofy treat, a cookie full of arsenic for the exploitative middle managers of the world.

Monday, December 02, 2013

Running Out of Karma: Seven Years Itch

Running Out of Karma is my on-going series on Johnnie To and Hong Kong cinema. Here is an index

After finding success in his return to filmmaking with 1986's Happy Ghost III, Johnnie To re-teamed with actor-writer-producer-Cinema City studio head Raymond Wong for a more conventional romantic comedy, loosely inspired by Billy Wilder's popular 1955 Marilyn Monroe vehicle The Seven-Year Itch. Wilder's film is an adaptation of the play by George Axelrod, who worked as a screenwriter and director as well as playwright. It's one of my least favorite of Wilder's films, and also my least favorite of Axelrod's works (he wrote The Manchurian Candidate, Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter and Breakfast at Tiffany's, and also directed the sublimely weird Lord Love a Duck). By reputation this remake might also be the least of all Johnnie To's 50-plus films but, while it certainly isn't great, it's not without interest. That's one of the nice side benefits of being an auteurist: even an artist's worst films can be interesting and enjoyable because of what hints or insights they might provide about the greater works. As a sidenote: this is actually one of Pauline Kael's more interesting objections to the Theory in her essay Circles and Squares: why is the mere act of recognizing an earlier, usually worse, use of a certain technique or trope interesting? Why should that be a critical value? I don't really have a good answer for that, but I think it might simply be an attraction for a certain kind of person, one who enjoys putting puzzles together. Finding an earlier example of a later line of dialogue or character type or whatever is like discovering a new piece, perhaps revealing not only more about the whole, but a fresh way of seeing the already-assembled pieces. It may not make the movie better, but it might make watching it more fun. But anyway, even Seven Years Itch isn't a particularly bad film, it's just not all that funny.

Raymond Wong, tall and skinny, bespectacled and awkward, cursed with a giant head (I say this with affection as a tall, skinny, bespectacled, awkward, giant-headed man myself) plays a mediocre salaryman living with but not technically married to Sylvia Chang (who sparkled as a tough as nails cop in the first half of the first Aces Go Places movie). His mother-in-law constantly berates him for not throwing the expensive wedding party that would make their union official, while his brother-in-law, the omni-present Eric Tsang, is constantly trying to borrow money and/or tempt him with prostitutes. Bored with his life and irritated at the way Chang always sings Chinese Opera with her gay cousin (this is literally how he's referred to throughout the film, if the subtitles are too be believed: either "Gay Cousin" or "Cousin Gay") and makes him the same boring breakfast, Wong begins daydreaming about infidelity. On a business trip to Singapore, he carries on a lengthy, montage-filled flirtation with a pretty girl in red stockings, who of course turns out to be a jewelry smuggler using him as an unwitting mule. Then things start getting weird.

Back home, Wong tries to reignite things with Chang. So he takes her to Singapore and tries to get her to dress and act exactly like the other girl. There are shades of Vertigo in these scenes, which are the best in the film. To playfully repeats the same camera set-ups and movements from the earlier sequence, but to comic effect as Chang plays the scenes all wrong, falls asleep out of boredom and Wong becomes increasingly frustrated. The role-play fails and Chang strikes up a flirtation with an older Chinese-American businessman (apparently named "Mr. Money"). Eventually Chang catches Wong with the other girl (she's come back to retrieve a smuggled ring she'd misplaced in Wong's bag which he'd then accidentally given to Chang as an apparent engagement ring, naturally) and leaves him for Mr. Money once they return to Hong Kong. A car chase ensues (with Wong getting sidetracked at a "couples only" hotel, where Chang catches him paying a prostitute so he can enter, as happens). Eventually Wong makes a big scene at the airport, which apparently fails to work and then it all ends happily.

It's that ending that's most relevant to To's later work, as the concept of the Grand Gesture will become a fundamental part of his romantic comedies. Needing You, in fact, follows much the same trajectory in its final third, with Andy Lau chasing after Sammi Cheng and trying to prove his love as she tries to leave Hong Kong with another, much richer, man (via boat this time rather than airplane, boats being both more cinematic and more final). Don't Go Breaking My Heart consists almost entirely of Grand Gestures, as Louis Koo and Daniel Wu compete for the love of Gao Yuanyuan with a series of increasingly elaborate creations, from Post-Its on office windows to massive skyscrapers. Most of the other romantic comedies feature them as well (the movie Koo makes in Romancing in Thin Air, the ghost's actions in My Left Eye Sees Ghosts, the final theft in Yesterday Once More). In To's films, the lover, almost always the man, has to prove himself worthy of the woman's affection. He has made some mistake that has kept them apart, and he must atone in as elaborate and as public a way as possible. In the later films, the heroine is unconventional, a prankster sort who doesn't fit in well with straight society. By making his grand gesture, the hero proves that he is willing to play the game with her, that he too cares little for the rules of social decorum.

The romantic comedies are told from the perspective of the woman, or at least it's her with whom we most identify. But that's not the case with Seven Years Itch. But for a few scenes of Sylvia Chang in cooking class (where she hears gossip from her married friends), almost every scene is built around Raymond Wong's character, and he's not a particularly likable one. Despite a few attempts at critiquing the kind of patriarchal ethos that attempts to justify infidelity (articulated by Tsang and Wong's male co-workers), the script wants us to root for him, to see his lying and conniving lustfulness as quaint and charming, or at best benignly ridiculous. To gives us a montage of lady parts, close-ups of breasts and legs and asses walking the streets of Hong Kong as they're ogled by men at every turn (including a recreation of the famous Marilyn Monroe subway grate upskirt-shot from Wilder's film, one that lingers for quite awhile on the unfortunate woman's improbably complex lingerie) that is somewhat reminiscent of a similar scene in Orson Welles's F for Fake, but it doesn't seem like that's nearly enough to defuse the boorishness of every male character in the film (Gay Cousin excepted). At times it seems like Wong and To very much want us to dislike the main character (while Chang plays the most emotionally coherent and likable person in the film), but the generic demands of Cinema City-style goofy slapstick prevent them from going all the way with it. Given a darker turn, they might have produced a cogent critique of Wilder and Axelrod's source material. Instead the film just gets lost in its ambivalence, while giving us a glimpse of better things to come.

Next Up: The Eighth Happiness

Sunday, December 01, 2013

This Week in Rankings

Since the last rankings update, I launched a new review series on Johnnie To and Hong Kong Cinema that I'm calling Running Out of Karma because I couldn't come up with a snappier title. So far I've covered his debut film The Enigmatic Case, John Woo's A Better Tomorrow II, Tsui Hark's Peking Opera Blues, Ringo Lam's Prison on Fire as well as the Happy Ghost series, of which To directed the third installment. Those reviews and more can all be found in the Index.

I've also recorded some more podcasts, four episodes of The George Sanders Show (The Big Parade and The Red & The White; Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure and Three Ages; Monsieur Verdoux and Bonfire of the Vanities; and Computer Chess and The Chess Players) and a new episode of They Shot Pictures on Claire Denis, focusing on Beau travail, L'intrus and 35 Shots of Rum.

These are the movies I've watched and rewatched over the last few weeks, and where they place on my year-by-year rankings.

Three Ages (Buster Keaton) - 3, 1923

Monsieur Verdoux (Charles Chaplin) - 4, 1947

The Red and The White (Miklós Jancsó) - 2, 1967

The Chess Players (Satyajit Ray) - 4, 1977

The Contract (Michael Hui) - 7, 1978

All the Wrong Clues (...For the Right Solution) (Tsui Hark) - 29, 1981

Aces Go Places (Eric Tsang) - 25, 1982

Aces Go Places II (Eric Tsang) - 15, 1983

The Happy Ghost (Clifton Ko) - 21, 1984

Happy Ghost II (Clifton Ko) - 35, 1985

Peking Opera Blues (Tsui Hark) - 4, 1986

Happy Ghost III (Johnnie To) - 23, 1986

Prison on Fire (Ringo Lam) - 25, 1987

A Better Tomorrow II (John Woo) - 35, 1987

Seven Years Itch (Johnnie To) - 40, 1987

The Eighth Happiness (Johnnie To) - 29, 1988

Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure (Stephen Herek) - 16, 1989

The Bonfire of the Vanities (Brian DePalma) - 41, 1990

Only Yesterday (Isao Takahata) - 8, 1991

Whisper of the Heart (Yoshifumi Kondo) - 5, 1995

Computer Chess (Andrew Bujalski) - 7, 2013

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)