1. Funny Face - One of my favorite musicals, as well as one of my all-time favorite movies (#45

last I checked), Audrey Hepburn stars in this Stanley Donen film as a bohemian bookworm who gets whisked away to Paris to be a fashion model for a famous photographer played by Fred Astaire and a magazine editor played by the fabulous-in-every-way Kay Thompson. Astaire's way too old for Hepburn, but it doesn't really matter. Far from being an anti-intelluctual "makeover" movie, where brainy Audrey is taught the true meaning of makeup and marriage, the film is a glorious, warm-hearted embrace of love, both as philosophical concept and as romantic pop song ideal. The film satirizes the pretensions of the fashion industry as well of those of the fashionable intelligentsia in favor of the primacy of human relationships. Both "style" and "philosophy" are masks, it's the soul that matters. Also there's music. Gershwin music and lots of it. Few films are as packed with great musical numbers as this one: from Thompson's earth-shattering

"Think Pink" to Hepburn's ravishing

"How Long Has This Been Going On?" and her brilliant

bebop dance parody to Astaire's umbrella toreador in

"Let's Kiss and Make-up" and his duets with Thompson (the wild

"Clap Yo' Hands") and Hepburn (the gauzily beautiful

"He Loves and She Loves").

2. Throne of Blood - Akira Kurosawa's expressionist adaptation of

Macbeth stars Toshiro Mifune as the tragic general who allows his (and his wife's) ambition to lead him into betrayal, murder and insanity. Much like he later did with

Ran, Kurosawa doesn't bother to adapt the language of the Shakespeare play into Japanese, but instead focuses on translating the raw emotions of the works into cinematic equivalents. Mifune is perfect here as the noble warrior who allows himself to be manipulated by a witch in the woods and his own scheming wife and then descends into a demented, elemental paranoia. Kurosawa modeled the look of the film on the Noh theater tradition (like he did with

Ran and

Kagemusha), with mask-like faces, a slow pace and a hauntingly eerie soundtrack. The dark dark, look of the film clearly has a lot in common with Orson Welles's own film of

Macbeth, but only Kurosawa could pull off a scene as lyrical and horrifically beautiful as the final battle sequence, when an entire forest comes alive to attack Mifune, his own soldiers turn against him and dozens, if not hundreds, of arrows are actually shot at the clearly terrified actor. the cast includes Takeshi Shimura, Minoru Chiaki and Isuzu Yamada who is very good as the Lady Macbeth character, if not quite as purely evil as Mieko Harada's Lady Kaede in

Ran. It doesn't get as much notice as Kurosawa's other masterpieces (let alone the Bergman films it beats out on this list) but it's as powerful as anything he ever made.

I just rewatched a bunch of what are generally considered the best films of 1957, and while this still is not my favorite film of the year and might not even be among my five favorite Kurosawas, I think it's absolutely worthy of its lofty spot on this list. It's even darker than

Sweet Smell of Success, with its vision of humanity as unchanging, trapped in a cycle of murderous ambition and venality entirely of its own making. I especially picked up this time on the interaction between prophesy and free will: everything Washizu does is his own choice, but would he have made those choices absent the prophesy? His troops turn on him at the end, but only because he's told them about the prophesy and they've seen the forest moving, if he hadn't told the, would they have fought back against the siege? It's telling that it's Washizu's act of mercy (letting the prince and Takashi Shimura go) that leads to his downfall: if he'd chased after and killed them, they wouldn't have led an army that knew how to get through the forest to attack the castle. It's this kind of thing that marks

Throne of Blood as the most tightly constructed of the top movies of its year. There's none of the haphazard sloppiness of

Wild Strawberries, or facile caricatures of

12 Angry Men or

Paths of Glory. Every piece of

Throne of Blood fits together perfectly. Almost a little too well. There's an airlessness to the film that is totally appropriate thematically (trapped as its characters are in an endlessly recurring loop) but that makes it a bit harder to love than some of the other films from this year (

Funny Face for example, though I can see why someone might prefer

Wild Strawberries for this reason, though,

like I said, that film didn't work for me at all).

The standout actors are Toshiro Mifune and Isuzu Yamada, and they're a perfect contrast in style: Mifune is constantly in motion, constantly retreating and bugging his eyes out. It's one of his most intense performances, he starts at an incredibly high level and stays there for the course of the film, never going over the line into camp or mere bluster. Yamada's Asaji, on the other hand, is all terrifying stillness. Her's is the most Noh-influenced of the performances, apparently. Donald Richie points out that it's the two female characters (Asaji and the forest spirit) that are the most Noh-like, which is interesting if you read the story as more than the tragedy of a hen-pecked husband, it's not just women that cause Washizu's downfall, it's the past itself, embodied in the ancient formalities and drives embedded deep within human nature.

3. What's Opera, Doc?

4. The Seventh Seal - Ingmar Bergman's masterpiece of Life and Death in the Middle Ages stars Max von Sydow as a returning Crusader who meets Death on a beach and challenges him to a game of chess in one of the cinema's better bits of capital "S" Symbolism. While the game is going on, the Knight gets to continue his journey where he and his squire meet a young family of traveling actors and together, they travel through the countryside in the wake of the Black Plague, where they meet crazy villagers, flagellant priests and various other medieval types. A beautifully filmed existentialist meditation, it also happens to be pretty hilarious. One of my favorite films and deservedly regarded as one of the essential classics of film history.

5. Pyaasa - This Bollywood film, produced and directed by its star, Guru Dutt, follows the decline and rise of a penniless poet, Vijay, with a complicated professional and romantic life. He wants to be a successful writer, but would rather reject the temptations of upper class bourgeois life that his ex-girlfirend has sold out and married into. More his style is the cute local prostitute, though she's got the whole immorality strike against her. Things get weird when Vijay disappears and is presumed dead and his writings become wildly popular, attracting a literally cultlike following.

I think this is an even more successful attempt at a neo-realist musical than Godard's

A Woman is a Woman (and maybe even

Pennies from Heaven), or at least it would be if it wasn't also so Expressionist. The jumble of generic and stylistic influences in the film is just plain weird, which makes me think of

Night of the Hunter as the closest analogue. Another director I though of, perhaps just because he's been on my mind lately, was Renoir, in the way Dutt paints a complete society of intersecting classes and moralities, complete with parallel and contrasting romances (Vijay and Gulabo, Meena and her husband, the masseur and Gulabo's roommate). The fantasy musical sequence also looks like something out of Powell & Pressburger.

The last half hour of the film or so can be taken any number of ways. I'm sure anyone who directs, produces and stars in his own film tends toward self-aggrandizement, but that's not how I took the messianic sequences at all. It's significant that Vijay absolutely rejects his followers. It's as if the resurrected Christ came back, looked around at the people who worship him and said "You guys suck, I'm outta here" then ran off with Mary Magdalene. The extended Christian allegory consists of more than just Dutt's repeated Christ poses (and a

Life magazine cover, which is pretty funny), but also in Gulabo as Magdalene (the fallen woman as true disciple) and the three denials of Vijay (by his brothers, his boss and his childhood friend).

6. Cranes are Flying - This Russian film directed by Mikhail Kalatozov follows a girl (Tatiana Samoilova in a wonderful performance) whose boyfriend leaves her to fight Nazis at the start of World War II. She ends up marrying his cousin and hating herself, but things more or less work out in the end. It's fairly conventional, plot wise, but wonderfully executed. From the opening sequence, with an eponymous bird's eye view of the young lovers, the film is stunningly beautiful. Quite impressive are a series of long tracking shots following the leads through massive crowds and a sequence where the girl finds the smoking remains of her bombed-out home. On the evidence of this film and they're later

I Am Cuba, Kalatozov and his cinematographer Sergei Urusevsky might be the greatest, or at least flashiest, masters of the moving camera in history.

7. Bitter Victory - One of director Nicholas Ray's more acclaimed films, in certain circles at least. Richard Burton and Curd Jürgens star as British officers sent to Benghazi to steal Nazi documents during WWII. It also seems that, before the war, Burton and Jürgens's wife had had a relationship and she may still be in love with him. During the attack, Jürgens fails to stab a Nazi according to plan, and Burton steps in to do it. On the return trip, Jürgens repeatedly tries to get Burton killed, either to cover up for his cowardice, or out of jealousy, or perhaps neither, possibly just because Burton keeps needling him about how much he wants Burton dead. One of the bleakest of WWII films, most of it is set in the North African desert, a landscape which has never looked more alien or abstract, lending its tragedy a vibe not entirely unlike that of

The Twilight Zone. Burton was in his prime as an actor; his completely cynical and utterly romantic hero is second only to his performance as the weary-to-the-soul CIA agent in

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. It feels like the end of the WWII film in the way

Touch of Evil is the end of film noir. A beautiful film, I don't think I can come close to plumbing its depths in this short a space, especially after seeing it only once.

8. Run of the Arrow - A great progressive Western from Samuel Fuller, the plot of which may be somewhat familiar. Rod Steiger plays a Civil War veteran who goes West and gets himself adopted into a Sioux tribe. Inevitably, his new people come into conflict with the US Army, and Steiger, after trying to peacefully resolve things, has to choose which side he's on. Yup, it's

Dances with Wolves, but instead of bloated, self-righteous and condescending, Fuller respects both cultures enough to show both their beauty and their brutality, all within a compact narrative that doesn't waste a single shot and moves forward with a ruthless momentum.

9. Tokyo Twilight - As dark and as epic as director Yasujiro Ozu gets, this brilliant film follows the melodramatic lives of a middle class Tokyo family. There's abortions and suicides and whores and more.

10. The Incredible Shrinking Man - A perhaps surprisingly brilliant sci-fi film about, well, a man who shrinks, incredibly. While vacationing on a boat in the ocean, our hero gets exposed to a radioactive cloud of some time, which caused him to slowly shrink. First to a size of 36 inches, where he stabilizes long enough to get really depressed and whiny about being small. Then he meets a circus performer named Clarice, herself slightly less than 36 inches tall. This scene was really surprising, it took an angle on a shrinking man idea that I never expected or would have thought of: that for him being 36 inches tall is an unendurable nightmare, but for a lot of people, that's just life. It put his complaining in an interesting, touchingly humanist perspective.

Later, his shrinking resumes until he's very tiny, smaller than a spider. The last large section of the film follows his attempts to survive as a tiny thing in the basement, where climbing a shelf is a Herculean ordeal and a leaky water heater can bring about a biblical flood. This is the action adventure portion of the film and its wonderfully done, suspenseful with practical effects that almost always work very well.

Once or twice a year, the snooty types at davekehr.com go on for pages and pages about how much they dislike Stanley Kubrick, and Jack Arnold, and this movie especially, are used as bludgeons against him. Watching the film, I wasn't really seeing the comparison aside from a couple beautiful shots (the opening water reminiscent of

Solaris and an iconic image of the hero standing on his boat, a lone silhouette facing an on-coming storm). But the final scene made it all clear: as the shrinking man shrinks he expands. Infinitely small, he encompasses the universe. It's

2001.

11. The Tall T - An Elmore Leonard story directed by Budd Boetticher and starring Randolph Scott. Scott plays a cheerful, down on his luck rancher who bad lucks his way into a hostage situation, as Richard Boone and two thugs kidnap a rich woman and her husband. The film, among other things, is a catalogue of masculinity, from Scott's regular guy doing what he can to make his own way with honor and dignity, the cowardly husband who sells his wife at first opportunity, Arthur Hunnicutt's stage driver braver than he is smart, Boone's villain who tries to act with honor and respect but hates his low class henchmen, those henchmen, Henry Silva's psycho Chink and Skip Homeier's callow Billy Jack. This last trio of characters is presaged in the film's opening scenes, when Scott visits his old boss. The boss is not particularly fond of his new ramrod (top ranch hand), who manages to be both mean, stupid and incompetent. As a matter of style, the film is a marvel. Not just the desolate locations or the low angles constantly framing the characters against the sky, abstracting and mythologizing them, but in the precision of movement both of the actors and the camera. In the intro to the DVD of the film, Martin Scorsese notes the peculiar ways actors move in a Boetticher film, as if every gesture or motion was freighted with meaning and proposes the theory that this grew out of Boetticher's experience as a bullfighter, where every movement in the enactment of a ritual. It's this ritualization that Boetticher brings to the Western, a stripping down to essentials in the service of generic purity.

12. On the Bowery - Lionel Rogosin's documentary of life among the drunk and homeless in New York's notorious neighborhood. It follows three days in the life of Ray, a rail road worker who comes to town with a pocket full of money and proceeds to drink everything that isn't stolen from him. The film follows a rough script, in the manner of a Robert Flaherty documentary, but the characters are all real Bowery men and women (Ray's friend Gorman died shortly after filming completed). It'd be easy, when talking about this film to get sidetracked into a discussion about what constitutes a documentary as opposed to a fiction film, but I defy anyone to watch it and see the world these broken and misshapen men lived in (and that men like them continue to live in) and tell me it isn't real. The film won the Best Documentary Award at the Venice Film Festival, that should be enough said. It's a ghastly, heart-breaking film, one that despite its tremendous influence has lost none of its power.

Interesting trivia for movie theatre geeks: in 1960 Rogosin founded the Bleeker Street Cinemas, one of the country's most influential art houses, partially to have a place to show his anti-apartheid film

Come Back, Africa.

13. The Tarnished Angels - Based on a William Faulkner novel, this Douglas Sirk film follows the relationship between a journalist and a Depression Era stunt pilot and his family, notably the hot wife he treats like crap. The lead performances are very good (Rock Hudson, Robert Stack and Dorothy Malone, reunited from

Written on the Wind) and Sirk's black and white 'Scope compositions are stunning.

14. A Chairy Tale

15. Witness for the Prosecution - Billy Wilder's adaptation of Agatha Christie's courtroom drama hasn't the least relation to any kind of realistic depiction of a murder trial, but thanks to two great actors (and one terrible one) it's a quite funny and entertaining genre piece. Charles Laughton (perhaps the ugliest, and greatest, actor in film history) stars as the defense attorney for Tyrone Power (who's terrible), who has been accused of killing a middle-aged widow. Marlene Dietrich plays the defendant's wife, the title character. Elsa Lanchester (Laughton's real-life wife) also stars.

16. Nights of Cabiria - Giulietta Masina gives one of the all-time great performances as the classic hooker with a heart of gold in this picaresque Federico Fellini film. There are three main sections in the film: an encounter with a celebrity, a trip with a massive crowd to a church for some religious festival, and an apparent discovery of true love. Each time Cabiria's hope and faith is raised, beaten down and yet somehow reemerges and she goes on to her next adventure. I suppose this makes her the ideal existentialist hero, trudging on with good humor despite all the horrible things that seem to unavoidably keep happening to her.

17. The Sweet Smell of Success - Acid indictment of the nihilistic amorality of the entertainment industry starring Tony Curtis in his best role as a small-time press agent (Sidney Falco) trying to ingratiate himself with big-time gossip columnist Burt Lancaster (J. J. Hunsecker), in one of his good performances. Directed in a crisply dark noir style by Alexander Mackendrick (

The Ladykillers), with cinematography by James Wong Howe. The screenplay's even better than the visual look of the film (high praise), written by playwright Clifford Odets and the great Ernest Lehman (

Sabrina,

North By Northwest).

Watched this again years after writing the above, and it's is pretty much how I remembered it: highly-stylized nastiness. One might say too much of either. Andrew Sarris famously said Billy Wilder was so cynical he didn't believe his own cynicism, I'm not sure that critique would apply here. Curtis is the protagonist, Lancaster the villain, but Sidney Falco is the more evil character, is he not? At least JJ Hunsecker loves his sister, twisted as that love may be. Falco lacks even that kind of humanity.

18. Show Biz Bugs

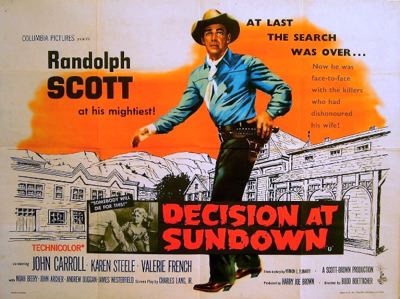

19. Decision at Sundown - The other Boetticher-Scott Western from 1957 is almost as good. Scott's performance here is a stunner, as happy-go-lucky as he was in the early scenes of The Tall T, it's a shock to see him so angry, so blinded by vengeance and ultimately broken by his own failure. The story's a much more complex societal portrait than Leonard's exploration of men being men, with Scott bent on avenging himself on the man he thinks stole his wife and caused her suicide. When he learns that the woman wasn't so innocent after all, he refuses to believe and that refusal, along with the treachery of the local lawmen (The Swede and Spanish, continuing the politically incorrect nickname theme from

The Tall T. Other connections: the hotel in this film is the same set as the one in

3:10 to Yuma, and

Yuma ends in Contention City, where

The Tall T begins, a few years before the railroad arrives) gets his best and only friend killed. It seems that while the fellow Scott's after is innocent of corrupting his wife, he has managed to corrupt the town of Sundown, and Scott's actions eventually inspire the townspeople to stand up for themselves and fight back. The ending is as bitter as anything you'll see: Scott is broken, illusions shattered, friend and wife dead; the town is free, but their own illusions are shattered, of their own complicity in their corruption (the exposure of the drunken judge is only the most obvious example) and their cowardliness in not standing up before people began dying; the ostensible villain though doesn't get to marry the vapid rich blonde girl he had his mind set on, but he does get to ride off with the town's redhead, the fallen woman who really loves him and saves his life. He's not the boss of the town anymore, but is there any doubt his ending is the happiest?

20. Jet Pilot - This I really enjoyed. I was worried about von Sternberg in Technicolor, but I don't think Janet Leigh, or John Wayne, have ever looked better (this was shot in 1950 which explain why they look so young). His mastery of lighting was apparently not confined to black and white. Though how much credit for that should be given to him, cinematographer Winton C. Hoch (a great Technicolor DP) or Furthman (a longtime Sternberg collaborator) is anyone's guess. The plot's completely ridiculous, but the reversals and innuendos are a lot of fun and the aerial sequences are as good as anything I've seen pre-

Top Gun.

21. Steal Wool

22. Curse of the Demon - I watched the shorter version for some reason, best to stick to the longer, original cut, called

Night of the Demon. Dana Andrews plays a scientist who goes to England to debunk a devil cult, but finds himself cursed and ultimately forced to accept the reality of the supernatural. Director Jacques Tourneur, returning to his Val Lewton roots (there's more than one allusion to his previous work), masterfully creates some low budget creepiness (no one makes hallways as menacing as Tourneur). Apparently he was quite upset with the shots of the demon that begin and end the film. He thought it should be left as more of a question as to whether the demon was real or not. I think it still works though. The amazing thing is that despite being shown in the first five minutes that the curse and the demon are real, the identification we have with Andrews is so strong that I find myself trying to come up with ways to explain away what is right in front of me. Tourneur is like a magician telling me exactly how his trick works, then fooling me with it anyway.

23. Le notti bianche - Lovely movie. Halfway through, I realized this was based on the same story as

Two Lovers, with Maria Schell has the apparently available object of Marcello Mastrioanni's affections. They end up being very different films, director Luchino Visconti gives this one an artificial kind of dreaminess James Gray isn't really interested in: the "neo-realist" touches that surround the story are unable to fully counter Mastroianni's innocent and ultimately tragic romanticism. Also, Mastrioanni dances to Bill Haley and the Comets and it is as awesome as you think that sounds.

24. Ali Baba Bunny

25. China Gate - It's an absolute travesty the condition this film is in on Instant Netflix. A panned-and-scanned abomination. Despite that, it's obvious this is another great Samuel Fuller film, a brutal look at racism and war with an ending that is first infuriatingly ridiculous followed by all kinds of surprisingly awesome. Angie Dickinson(!) plays a half-Chinese(!) single mom(!) named Lucky Legs(!!) who has to lead a squad of the French Foreign Legion through the Vietnamese wilderness to blow up the supply route from China. Trouble is, the demolitions guy in the troop just happens to be her ex-husband, who abandoned her when their son was born and turned out to look more Chinese than American. Dickinson, despite being the last person you'd expect to find in a gritty Sam Fuller war movie, is excellent throughout, showing exactly the intelligence and toughness that would make her one of the great Hawksian woman two years later in

Rio Bravo. Nat King Cole, of all people, plays a key role as one of the soldiers, an American who kept fighting after Korea because he enjoys "killing Commies" so much. He gets a phenomenal scene where he steps on a spike but due to the proximity of some "Commies" can't cry out: he just twists in agony. Lee Van Cleef shows up at the end as the main villain, another half-Chinese who tries to convince Dickinson to run away with him. Basically, everyone in the film wants to marry Angie Dickinson except the man she loves, a racist idiot with pretty much no redeeming qualities. Tell me Samuel Fuller doesn't know people.

26. Men in War -

Existential, elemental. The men are attacked by the grass, the tress, the hills, the sky, the earth and, most terrifying of all, other men. Anthony Mann's Korean War film with Robert Ryan and Aldo Ray follows a doomed platoon as they try to make their way past the (almost completely unseen) enemy. As terrifying as anything Mann ever did, like an extended version of the apocalyptic finale of his 1958 Western

Man of the West.

27. Kanal - I liked the only other Andrzej Wajda films I've seen,

Ashes and Diamonds, though I thought it was a bit overstuffed with Style! and Symbolism!, which is strange because generally I like that kind of thing (

Cranes are Flying, for example, is all Style!, though less so with the Symbolism!). This film is a bit more subtle, though that hardly seems an appropriate way to describe a film that equates war with Andy Dufresne's escape from Shawshank, except instead of crawling through "five hundred yards of shit smelling foulness I can't even imagine, or maybe I just don't want to", Wajda's freedom fighters are trapped there, seemingly for eternity. The first third of the film is typical war movie stuff, introducing the characters and their relationships and making clear the hopelessness of their situation, in the waning days of the Polish revolt against the Nazis. Soon the small band is cut off and their only escape route is through the sewers of Warsaw, and ancient labyrinth that looks back to Dante and ahead to

Apocalypse Now. Wandering in the darkness, wounded and poisoned by the noxious gasses, the group splits and splits again, until we're left with only a couple small groups of soldiers: a woman who knows the sewers well leading her dying lover to the sea, a composer who loses his mind, doomed to wander the tunnels blowing a haunting tune on an ocarina, and most poignantly, the platoon's Lieutenant, who, with an attendant, makes it to safety only to find the platoon had been left behind him long ago. In a film so relentlessly hopeless, the Lieutenant's final act, descending again into hell to try to rescue his men, is miraculous. He knows they're doomed, he knows

he's doomed. But he does it anyway. It's as pure an act of heroism as you'll ever see in a film, done with resignation and horror.

28. The Lower Depths - I'm going to start by saying that this isn't the least bit "filmed theatre", at least not as I understand the term. To me, it means a more or less direct translation of a play to film, with little of the technique we generally use to differentiate the experience of watching a film from that of watching a play. "Filmed theatre" is static, with little in the way of camera movement; it films a flat space perpendicular to the camera to create the effect of a proscenium arch; the actors are frontally focussed, addressing an imaginary audience; there's not much in the way of analytic editing to divide and/or explore the theatrical space, either for dramatic emphasis (closeups at big moment) or just to create a rhythm of varied looks. When I think of "filmed theatre" I think of the very earliest, pre-Griffith et al days of cinema, when filmmakers really would just plop a camera down and act in front of it with the goal of making the viewer feel like they were nestled into an orchestra seat at a broadway show. Of course, very few films that would rightly be called "filmed theatre" made since 1912 or so really fit with so strict a definition, but usually when I see that term, I expect to see a lot of those elements, at least significantly more than in a film shot and cut in a standard way.

Well, The Lower Depths is about as far from that idea of "filmed theatre" as one can get. Director Akira Kurosawa, adapting a play by Maxim Gorky, takes a very talky play limited to essentially one location and creates a tour de force of directorial style. He basically throws every trick in his playbook at the screen in an attempt to cinematize the play, and the result, visually at least, is pretty breath-taking. Kurosawa was always a master of composition, especially the relative arrangement of characters within the frame (a skill he learned no doubt in training to be a painter), and this is perhaps his most visually dense film. He pulls off a trick I've only ever seen done as successfully in films by Hou Hsiao-hsien, where a shot of a few figures talking will be held for quite awhile before you realize exactly how many characters there are on-screen: the shock of recognition after looking at a shot for three minutes and realizing there's actually a character sitting in the bottom left corner is fun, having that previously unseen character suddenly leap to life and begin berating the other characters is genius. There's one shot early in the film that appears to feature three characters in conversation, then you discover a fourth, a fifth, a sixth and finally you realize just how densely packed the slum these wretched people are living in really is.

|

|

How many characters do you see?

|

Kurosawa also avoids theatricality by filming the main set, a common room in a shack where a number of drunk, sick and for all intents and purposes homeless people crowd together, roughly parallel to the axis of the camera, keeping the whole depth of field in focus. Instead of a proscenium view with the actors arrayed before us as on a stage, we get a three dimensional space with the characters piled on top of each other yet separated, all on their own planes. In final third of the film, though, Kurosawa returns to the same common room and films it perpendicular to the camera, but closer up. The effect is to bring the characters together (they're united in their common shock at the preceding events) in a way they weren't at the beginning of the film.

There's a lot more: the camera moves more than usual with Kurosawa (certainly more than it would move in his later films), he films at unusual angles (there's a cool shot early in the film with the Laughing Samurai from Seven Samurai: Kurosawa gives him a low angle shot with a smooth movement in and simultaneous tilt up, a heroic framing against the sky, ironic considering his doubtful status as a penniless ronin). Kurosawa's compositions are always interesting, posing characters at odd, dramatic diagonals, in diamond-shaped groups of four where no one looks at anyone else, on different levels not just in depth but in height as well.

The acting is uniformly pretty great, featuring a ton of Toho contract players, many of which are recognizable from other Kurosawa films, especially Seven Samurai, The Hidden Fortress, Throne of Blood and Yojimbo. Toshiro Mifune is, as always, the ostensible star, but the film belongs to Hidari Bokuzen (unforgettable as Yohei in Seven Samurai), who plays a passing old man who who seems wise in dispensing grandfatherly advice but is probably concealing some horrible secret.

Unfortunately, while the film transcends what I would call "filmed theatre", it does suffer from what a lot of play-based films do, that of being too written. See, it's not the visual style failing to "open up" the film that is the problem, rather it's a matter of everything in the film being put into words. Theatre is a verbal medium, just as film is a visual one, and in a play you expect the characters to say what they're thinking in interesting and dramatically compelling ways. To a certain extent, that kind of thing is expected in a (talking) motion picture as well, but the problem I've been having lately with a lot of very writerly films is that the fundamental wordiness of the scripts not only gums up the visual artistry of the filmmaker (not in Kurosawa's case of course, but in others) but it subverts the kind of reality that's most appealing on film. (Why I should react this way to the "writtenness" of this film, or Marty or The Big Knife and not the very stylized and writerly films of, say, Whit Stillman, Quentin Tarantino, Ben Hecht, Woody Allen, etc is a question I don't yet have a satisfactory answer to).

In the end, like a lot of these over-written films, The Lower Depths just feels phony. And worse, it's the kind of phony with a lame message: that it sucks to be poor and live in a slum that's easily mistaken for a garbage dump because the people that live at the bottom of society are just mean and awful and there's no hope so just get drunk because you're going to die of tuberculosis anyway so you might as well enjoy it. Maybe that's the difference: The Lower Depths, like the Paddy Chayefsky and Clifford Odets films I haven't been enjoying, is trying to convey a social realist message, but the unreality of the writerly dramatic style is creating a disconnect, whereas the writerly films I do like are generally not the least bit concerned with reality or trying to convey a socially conscious message. The verbal form is conflicting with the thematic content, creating an overall feeling of phoniness.

29. An Affair to Remember - Leo McCarey's remake of his own 1939 film

Love Affair stars Deborah Kerr and Cary Grant as a couple who meet on a cruise and fall in love, despite each being engaged to other people. After the cruise, they agree to meet six months later at the top of the Empire State Building. A classic story, decisively influential on many a film, including

Sleepless In Seattle and

Before Sunrise, the film itself is quiet and classically styled, with an elegance and earnestness that's been lacking in romantic films for decades. Kerr and Grant are quite good, as they always are.

30. Forty Guns - Barbara Stanwyck stars in Samuel Fuller's Western about a "high-ridin' woman. . . with a whip!" Three bounty hunter brothers show up in a small town in search of a fugitive, who happens to be one of the eponymous gunmen Stanwyck employs to run her cattle empire. The oldest brother (Fuller's ever-constant Griff, played by Barry Sullivan) also manages to start a feud with Stanwyck's little brother, who's rather psychotic. But, of course, Griff and Stanwyck fall in love, with unfortunate consequences for all of their brothers. The dialogue's got some famous double entendres, and Fuller uses the 'Scope frame well, with wide Western vistas and some tense showdowns. If any director was made for the Western, it was Samuel Fuller. The studio enforced ending is pretty hilarious too.

31. The Three Little Bops

32. Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? - I guess it should have been obvious that Tony Randall was a poor man's Jack Lemmon, seeing as how he played the Lemmon role in the TV version of

The Odd Couple, but somehow I'd never connected the two before. However, the opening of this film is so reminiscent of

The Apartment, the Billy Wilder film Lemmon would star in three years later, that the comparison finally became obvious enough for me to see it. Randall stars as an advertising writer about to lose his job who hits on the idea of getting an actress' (Marilyn Monroe-ripoff Jayne Mansfield) endorsement for his firm's big client, a lipstick company. When he goes to ask her, she uses him to make her muscle-bound boyfriend Bobo Branigansky (love that name) jealous. Word gets out and overnight Randall becomes a world famous lover. This is great for his professional career and standing with women and teenaged girls in general, but lousy for his girlfriend, who almost kills herself doing pushups in the hope they'll give her a more Mansfieldian figure. This being a Frank Tashlin film, there's a lot more craziness than that (some of the funniest bits being the commercial parodies that open the film). It has a whole lot in common with his previous Mansfield film,

The Girl Can't Help It, and like that one there's a serious grounding of melancholy and 1950s dissatisfaction under all the zaniness. But I don't think Randall's got the depth to quite pull that off, though he is better than Tom Ewell was in the earlier film. It's a shame Tashlin couldn't get Jack Lemmon for those parts, he would have been perfect.

33. Band of Angels - Raoul Walsh epic of the pre-Civil War South with Clark Gable as a rich scoundrel who buys Yvonne DeCarlo (who has only recently discovered she's half black and therefore saleable). They attempt to fall in love, but the past won't let them. Sidney Poitier plays Gable's chief slave, a man who has a complicated love-hate relationship of his own with Gable. The whirl of associations and meanings as layer upon layer of personal history is unveiled, as every character is masked, unmasked and unmasked again like an antebellum

Scooby-Doo episode is dizzying. No one is good, but there's plenty of evil and no one can stand to be around or respect anyone else, and asking them to do otherwise is not only offensive, it's impossible. In the end, there's no solid ground to stand on, just 30 miles of swamp in every direction. Might as well say "Fuck it" and hop on a boat with Clark Gable to live life as a Caribbean pirate wench or something.

34. 3:10 to Yuma - Delmer Daves's Western, based on an Elmore Leonard story, reaches its peak early on, in a quiet, sad scene between Glenn Ford's murderous gunman and a local barmaid played by Felicia Farr, two lonely people spending an afternoon pretending they still have illusions. The rest of the film is clever, with Ford tempting Van Heflin's rancher again and again in a futile effort at escape. Heflin never gives in and in the end that dogged honorability is what saves him, though we never really believe he would give in, despite the sweaty and twitchy performance. Ford is the acting star here, as charismatic as I've ever seen him, a perfect Leonard villain, great at talking and with a code that, while not exactly moral or honorable, is at least a code.

35. Nightfall - A low key noir that's more about character than atmosphere or narrative pyrotechnics. Aldo Ray's gravelly voice is a perfect fit for his weary everyman, on the run longer than he can remember for a crime he didn't commit. Anne Bancroft matches him sigh for sigh. Brian Keith and Rudy Bond create two wildly different types of criminal, Bond the giggling psycho, Keith the scarier for him air of calm reasonability. The violence is sparse but demented and cruel in the way of late noir. Not as scary or fraught as the darkest noirs, director Jacques Tourner instead brings out the melancholy of the wrong man story. It might be the saddest noir I've ever seen.

36. Saint Joan - Otto Preminger's meticulously roving camera and lawyer's brain form a perfect match with George Bernard Shaw's talky Joan of Arc play, which amounts to little more than a series of arguments, usually between only two characters at a time. The relentless tracking though, following and reframing the characters as the dynamics of argument shift, from long shots separated by miles of space to close ups with disembodied heads floating on top of each other, gets about as far from "filmed theatre" as you can get in a straight adaptation. Jean Seberg got disastrous press as the lead ("I have two memories of

Saint Joan. The first was being burned at the stake in the picture. The second was being burned at the stake by the critics.") but I thought she was fine. Her inexperience shows, but that's appropriate for the character, which I assume is why she was cast in the first place. The most interesting performance is by Richard Widmark as the Dauphin, who he plays as a mostly pleasant combination of Jerry Lewis and the Cowardly Lion.

37. Ill Met By Moonlight - A bit better than

Pursuit of the Graf Spee/Battle of the River Plate, but like that other late Powell & Pressburger film, it feels oddly out of date. And not in the good way that all the best P & P films are, taking place at once in a specific place and at an abstract, universal time. No, it's out of date in the way that

Colonel Blimp explores, critiques and transcends. All three films deal more or less with soldiers holding to an outmoded code of honor, in spite of the horrors of modern warfare. While that tension, between the old and the new, is the subject of

Blimp, it's simply the given of the two later films. But

Blimp presents the counter-argument, that this war against the Nazis is a wholly different kind of war.

Moonlight's Nazi, though, is all honorable nobility. Sure, he tries some trickery to escape the British-led commando unit that has kidnapped him and is attempting to smuggle him from Crete to Cairo, but there's never the least indication that he's capable of any actually scary evil (compare this film's vision of war with Wajda's or Mann's 1957 offerings, for example). It's an odd thing: P & P made some convincingly scary Nazis for

49th Parallel, a film that was explicitly propaganda. I wonder if they thought that was a flaw, to be corrected years later? Anyway, besides all that, the film is an enjoyable wartime adventure, with kooky Cretans and Powell's always-pitch perfect understanding of landscape and the way it shapes and dominates characters.

38. Il Grido - This is the first pre-

L'Avventura film by Michelangelo Antonioni film I've seen, and while it's not bad at all, it doesn't hold a candle to his other work, at least not for me. I guess it's more in the "neo-realist" vein than his later classics (complete with allusion to Charlie Chaplin), it stars American Steve Cochran as a guy who gets dumped by his girlfriend (Alida Valli) and takes off on the road with their daughter in search of a job or something. His travels lead him first to

Marty's Betsy Blair who appears to be his back-up girlfriend, but he takes off after her nubile young sister makes a pass at him. He next lands at a gas station her he romances the very pretty and willing owner, but leaves when having the daughter around complicates things (he sends the girl back to Valli and takes off on the road again). Finally he finds himself living in a shack down by the river with a sexy prostitute. Unable to find meeting in the arms of all these pretty women, he heads back to his hometown, only to find more existential despair. It's a pretty bleak and vaguely silly film, that would have worked a lot better if it had a different ending, or maybe if Cochran didn't have a 007-type effect on every beautiful woman he met. But still, pretty ladies + angst = Antonioni.

39. I am Waiting -

Docks of New York immediately came to mind for me, both with the initial setup (guy finds sad girl on a pier, takes her back to a bar) and in the neato compositions by director Koreyoshi Kurahara. Like with

Nightfall and

3:10 to Yuma, I liked more the relationships between down and out characters than the noir genre machinations that the rest of the film follows. The bar in particular is a great setting for the bottom of the barrel, where all these ruined people wash up. What is really interesting was the web of interconnections the film draws in the end. It's all wildly improbable, but sublimely so. It's not just nihilism or doomed romanticism we find at the end of the line, but that in the end, everything is connected.

40. Wild Strawberries - There's a scene fairly early on in this movie that pretty much sums up the problem I have with it and Ingmar Bergman in general. During the first of Victor Sjöström's flashbacks, we see his "secret fiancee" get kissed by his good-for-nothing brother. (We know the brother's good-for-nothing because the dialogue helpfully tells us several times that he is, in fact, good-for-nothing.) After the kiss, the girl, Sara, is anguished. We know this because she cries "Ah! I am anguished!" (or something like that, I don't remember the dialogue exactly); because Bergman rushes in for a closer shot of her face, wearing an actorly expression of Anguish; because the kiss has spilled the Wild Strawberries she had been gathering to give her uncle, smearing her white dress--this is Symbolism (we know because Wild Strawberries is also the title of the film): her generous strawberry gift has been ruined by a selfish act, through this same act she has lost her innocence (despite the black and white, we can assume her white dress is now smeared red, please don't make me explain what that is Symbolic of). Basically, Bergman is never content to let things be subtle, he will let you know exactly what he means in every way he possibly can in every scene. The film is utterly lifeless, over-determined and surprisingly sloppy.

Another example: we are told repeatedly that Sjöström's is cold, a heartless old bastard, yet all we see is a slightly cantankerous, wistful old man who is nothing but nice to pretty blonde girls and anyone else he comes across. So when, at the end, he's learned to be nice and wistful, we haven't learned anything. We've gone on a journey through space and time but not character, as Sjöström's flaws are only asserted in dialogue, never depicted. The flashbacks do nothing to deepen his character, they show how he was betrayed by women, but not why (we are told his marriage is bad, but we don't ever see any evidence of it, or ever he and his wife together). This assertion as a substitute for dramatization applies to the character of Sjöström's mother as well: we spend a long scene with her only to be told later that she's "as cold as ice". But on the evidence of the scene we just watched, I thought she seemed remarkably pleasant for a 96 year old lady that no one ever visits. This also applies to Gunnar Björnstrand as Sjöström's son. Ingrid Thulin tells us about his horrible crime: he is also a cold bastard, our evidence is that when she tells him she's pregnant he gets mad and says it's evil to bring a child into the world and he wishes he was dead. This is clearly a man with serious psychological issues, or it would be if we actually took this nonsense seriously. Fortunately, we must not, as the whole situation is resolved in Björnstrand's only other scene, where he explains that he now will have the kid because he can't live without Thulin. Yippee! Glad that's resolved!

I did like the opening dream sequence, with its overt reference to The Phantom Carriage and a neat little visual trick where Sjöström is walking along a sidewalk, past a lamppost whose shadow apparently falls on the side of a building, but when Sjöström passes, he moves in front of the shadow instead of through it--the shadow is painted on the wall. This opening sequence owes a huge debt to Cocteau and Buñuel, though it never reaches their height of surreality (Fellini does better in the opening dream of 8 1/2). The rest of the film as well does follow a kind of dream logic, I kinda like that Sjöström's flashbacks aren't really flashbacks (because they're of things he couldn't have seen) but rather Scroogelike ghostly visitations, but even that logic gets screwed up in the second flashback: Sjöström and his examiner ("You've been accused of guilt." Blech) are watching Sjöström's wife hook up with some dude in the woods in what first looks like rape but is apparently just infidelity. Our POV is Sjöström's, looking out in long shot at the couple far off in the distance. But Bergman repeatedly violates that POV by cutting to close-ups of the couple as they struggle and then talk. And it isn't just that Sjöström has moved closer, because those close shots are intercut with reverse angles of Sjöström and the examiner in the same distant location, with repeated POV shots of them again looking at the couple far off in the distance. You could probably get away with applying dream logic to that, except the examiner helpfully explains in dialogue that what we are seeing is a flashback, that Sjöström once stood in this same spot and saw and heard this exact scene. So the long shot and dialogue is the flashback while the closeups are the dream? I don't buy it. I think it's just shoddy filmmaking.

Seventh Seal is soooo much better than this.

41. The Truth About Mother Goose -

42. The Curse of Frankenstein -

43. Paths of Glory - One of my favorite, and not coincidentally, one of the least misanthropic, of all of Stanley Kubrick's films is this courtroom drama in which Kirk Douglas tries to save three men from being executed for cowardice in the wake of a disastrous and idiotic offensive during World War I. Kubrick directs in a crisp deep focus black and white, and his depiction of the battle, a long tracking shot of the horrors of trench warfare, is one of the most powerful scenes he ever shot. All the actors are quite good, but Douglas especially stands out as the idealistic warrior-attorney. The film's final scene, that of a young girl singing beautifully before a barroom full of rapt soldiers is the most romantic and humanist thing Kubrick ever did. He even went and married the girl.

This had always been one of my favorite Kubrick's, but I hadn't seen it in quite awhile and was really dreading the rewatch. That quote about Wilder applies perfectly here. That's really what the coda is all about, right? 80 minutes of righteous sarcasm aimed at the ignorant jackasses who run the military followed by Mrs. Kubrick's singing uniting humanity. Adolphe Menjou seems to be the only one who knows how silly the black-and-whiteness of the scenario really is, allowing himself to have some fun with his character. Everyone else plays it like this is the movie to end all wars. Except Timothy Carey, whose eye-rolling weirdness is just plain bizarre, but I suppose might be considered acting in some parts. The less said about Kirk Douglas's bluster the better. Stupid people do stupid things and smart people get indignant but can't do anything about it. But take heart audience because WE are the smart people. Let's all sing a song about how great we are.

44. Silk Stockings -

45. The True Story of Jesse James - The third major Jesse James film I've seen, after Andrew Dominik's

The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford from 2007 and Samuel Fuller's debut film,

I Shot Jesse James. Fuller has a lot in common with director Nicholas Ray, as both are revered by auteurists for their profoundly personal films made largely within the confines of the studio system, and their careers are roughly parallel, running from the late 40s to the early 60s (Fuller lasted a bit longer, making a pair of significant films in the 1980s). Unlike those other two James films, which focus as much or more on James's killer, this film is more of a straight biopic, as, after a opening sequence establishing a robbery gone wrong and James's mother lying sick in bed, various characters relate the major events of James's life in 15 minute episodes. The character, as Ray apparently sees him, is not the charismatic hero of legend, but rather an angry young man, driven by the atrocities his family suffered during the Civil War to revenge himself on Yankees by stealing their money, first from banks, then trains. He's barely more sympathetic than a traditionally psychotic outlaw like Billy the Kid. Part of that, though, may be casting. James Dean was apparently supposed to play the part, but died before the film could be made. A wholly inadequate Robert Wagner takes his place, and resembles more a pretty, empty suit than a legendary outlaw. Jeffrey Hunter is better as Frank James, though the age difference between him and Wagner doesn't seem close to being correct. The best part of the film comes at the end, after Ford has killed James and the James household is rushed by curious townspeople. Frank James chases them away, but not before a couple of on-lookers help themselves to some Jesse James memorabilia. As the camera pulls away from the house, a homeless drifter walks along singing the "Jesse James" folksong. His body yet to turn cold and already his true story is transformed into mythic art.

46. Bridge on the River Kwai - Alec Guinness stars in this David Lean epic about British soldiers in a Japanese POW camp during World War II who are forced to build the eponymous bridge. The battle of wills between Guinness (as the leader of the British) and Sessue Hayakawa (as the camp commandant) is wonderful, with great performances from both, especially Guinness as his character descends from hard-nosed, stiff-lipped ideal of British manliness to lunatic obsessive. The film is quite nearly ruined, unfortunately, by a terrible performance (of a terribly-written character) by William Holden as an American soldier in the camp who escapes and leads the return to liberate the camp. In no way is anything involving Holden in this film any good at all. His character is written and acted seemingly as a parody of what the British think Americans are like (compare Holden here to Steve McQueen in

The Great Escape). It's really unfortunate, considering the rest of the film is as good as anything Lean ever did.

47. Go Fly a Kit -

48. The Tin Star - Reading through some other reviews of this Anthony Mann Western, I see a lot of the same words: simple, standard, annoying kid, great Fonda, entertaining, well-made, good music,

Shane. These are all apt descriptors (except for the music, I found Elmer Bernstein's score to be pretty overblown). I prefer the ambiguity of the Mann-Stewart films (not to mention Mann's 1958 Western with Gary Cooper, the apocalyptic

Man of the West) to this kind of generic (albeit good) storytelling. There's always a lot to like in an Anthony Mann film, and his visual technique here is as good as ever (there are some killer shots his smoothly reframing camera finds, and also a sweet little track through swinging saloon doors, anticipating

The Passenger, perhaps) but for me, this is one of his least interesting. It feels like he's going through the motions rather than pushing the envelope. As with

Shane (and

High Noon, another film about how townspeople aren't worth their sheriffs' heroism, though Mann can't even bring himself to that level of cynicism here, leaving us with an (intentionally?) absurd ending where all is forgiven and the men of action are reintegrated into the (finally) grateful society), it can fairly be called a Western for people who don't like Westerns. Give me the moral complexity of

Decision at Sundown, the spare elegance of

The Tall T, the strange beauty of

3:10 to Yuma, the anguish of

The True Story of Jesse James, the savage righteousness of

Run of the Arrow, or the sheer lunacy of

Forty Guns over

The Tin Star's generic solidity any day.

49. Fire Down Below - A weird one, the first half dark romantic comedy, with Robert Mitchum and Jack Lemmon doing a kind of riff on Bogart and Brennan in

To Have and Have Not, the second half a disaster film with a race against time to free a trapped sailor from a ship that could explode at any moment with Napoleon from King Vidor's

War and Peace fretting nervously about the dock. In between, as usual there's Rita Hayworth. Hayworth's never been one of my favorite screen sirens, she's a fine actress, and a good dancer (her Fuck You! calypso dance at Mitchum here is easily the best scene in the film), but she's never appealed to me as much as say, Gene Tierney or any number of other, similar stars of the 40s, and at 39 in this film, she's a bit past her (overrated) prime. So it's a little hard to see what Lemmon, all youthful energy and passion, sees in her. Mitchum makes it work though. He looks like his prime has past as well.

50. The Rising of the Moon - John Ford goes to Ireland directs an anthology film with a cast of mostly unknown theatre actors in an attempt to jumpstart an Irish film industry. The film flopped and didn't do Irish filmmaking much good, but it is a decent enough movie. The first story is the best, combining two major Ford obsessions: drinking and nostalgia for the past in the face of modernization. The second story is a fun bit of Ford-brand comedy, about a train that keeps trying and failing to leave a station because of those quirky Irish. In the third story, Ford indulges his expressionist side, filming the escape of an IRA hero from the gallows with absurdly canted angles. It's not an unpleasant film by any means.

51. Love in the Afternoon - One of the mellower Billy Wilder romantic comedies, starring Audrey Hepburn as a young girl out to seduce the way too old Gary Cooper. Hepburn's the Veronica Mars-esque daughter of PI Maurice Chevalier, who's be hired to prove that Cooper, a notorious womanizer, has been sleeping with his client's wife. Hepburn falls in love with Cooper and pretends to be a slutty socialite to make him jealous. Hepburn's as great as ever, but Cooper's not only too old (creepy!), but neither comic nor romantic enough to be the star of a romantic comedy.

52. Let's All Go to the Lobby -

53. The Edge of the City - The first two-thirds of this Martin Ritt film is the story of a friendship between two dockworkers, a shy young man with a shady past and poor telephone manners (John Cassavetes) and his gregarious family man boss (Sidney Poitier). That this is an interracial friendship at the dawn of the Civil Rights era is obvious, but never commented upon: both characters are allowed to be people instead of arguments. But then, inevitably, the social conscience comes out and drama is manufactured as a racist villain does something dramatically villainous. I don't know, though, whether to blame the film for ultimately reducing Poitier's character (along with that of his wife, played by Ruby Dee) to a signifier of racial injustice, or society itself for ultimately being unable to see certain people as anything but props in an argument. In the meantime, these three actors do great work.

54. Les Girls -

55. The Enemy Below - I admit, I chuckled when I saw "Directed by Dick Powell", but the guy does a creditable job with his action sequences (though I wonder if that was all the second unit guy, Arthur Lueker (

42nd Street, Jezebel, China Gate). The philosophic "war is hell" monologues are sophomoric but relatively inoffensive, and the sub action is well-coordinated and suitably suspenseful. It's isn't

Das Boot or

Red October, but it's a reasonable facsimile. I liked Mitchum's other "Below" movie this year better.

56. Time Without Pity -

57. Night Passage - This James Neilson-directed Western supposed to be another Anthony Mann - James Stewart film, but according to IMDB, Mann quit the project because he didn't like Audie Murphy, Stewart's costar. I'm pretty sure I don't believe that. Anyway, it has a lot of similarities with the other Mann-Stewart films, with Stewart playing an experienced gunfighter who may be out for revenge, or may just want to be left alone but is forced into solving a town's problems anyway. He's great, like he always is, and Murphy is particularly bad either. Some nice train sequences, but nothing too spectacular.

58. The Wings of Eagles - A John Ford biopic about naval aviator turned paralyzed screenwriter Spig Wead. Wead and Ford were friends, and it shows in this rather tame film. Sure, Wead has his bad qualities, but he's still a helluva guy. Ward Bond does a hilarious Ford imitation as the Hollywood director Wead goes to work for, and like all Ford films, there are some really terrific moments, but they're way too few and far between.

59. Les Mistons - This short film by François Truffaut follows a group of delinquent boys as they torment a young couple in love (Gérard and Bernadette) over the course of a summer. At 17 minutes long, it's a slight but interesting film, famous mostly for the icky sequence in which the boys sniff Bernadette's bicycle seat. Eww.

60. Peyton Place - Like

Twin Peaks, but without the surrealism. The seedy underbelly of small town New England that no one wants to talk about but that we all know is always bubbling under the surface. Infidelity, murder, rape incest, skinny dipping, make out parties, and all that. The film's at its best in the early sections, filling out the details of the world with nice little character moments for Mildred Dunnock as the school teacher who doesn't get the principal job, Russ Tamblyn as the sensitive shy boy next door and Diane Varsi as the main character, a girl smart enough to see the hypocrisy around her and want to get out of town as fast as she possibly can. When the melodrama starts rolling, with lascivious revelation after revelation, all culminating in a big courtroom scene where Lloyd Nolan gets to give a speech about the evils of gossip, the movie becomes a lot more fun and a lot less real.

61. 12 Angry Men - Quick thoughts on rewatching 12 Angry Men:

Why are those guys yelling?

Isn't it nice how everyone changes their verdict in order of their likability as human beings? The last four are the racist, angry dad, robot capitalist and wishy-washy ad guy while the first four to vote not guilty are liberal superman in the white linen suit, super nice old man, nice quiet guy from the slums and I Believe In America immigrant guy.

There's no way any of this would be allowed to take place in a real jury room, would it? Let me check the wikipedia. . . .

(Sonia Sotomayor) told the audience of law students that, as a lower-court judge, she would sometimes instruct juries to not follow the film's example, because most of the jurors' conclusions are based on speculation, not fact. Sotomayor noted that events such as Juror 8 entering a similar knife into the proceeding, doing outside research into the case matter in the first place, and ultimately the jury as a whole making broad, wide ranging assumptions far beyond the scope of reasonable doubt (such as the inferences regarding the "Old Woman" wearing glasses) would never be allowed to occur in a real life jury situation, and would in fact have yielded a mistrial.

Is it OK to have a courtroom drama with a criminally bad defense attorney if the characters talk about how bad they think the defense attorney is? This can't have been that difficult a case to handle, right? Isn't checking if the eyewitnesses wear glasses taught on the first day of criminal trials 101?

It would have been interesting if the film actually dealt with race. I mean, everyone turning their backs on racist guy's hate speech is nice and all (let's all ignore racism! that'll shame it into going away!), but the kid in question isn't even specifically ethnic at all. I thought he looked Greek or Italian, wikipedia says he's often Puerto Rican. I guess twelve white guys sitting in judgement on a black kid from the slums would have raised more complicated issues in 1957. Edge of the City at least tried.

The acting's good, I guess. Fonda doing his Fonda thing. Maybe one of his 15 best performances. I dug Martin Balsam as the whiny foreman, especially in the beginning. I lost interest in his "hey this is a play so i get to give a speech now" speech though. Lee J. Cobb once again does Lee J. Cobb things. I wonder if there's a movie with Lee J. Cobb and Rod Steiger together. That'd be one exciting bit of showy method shouting, wouldn't it? (edit: On the Waterfront!) E. G. Marshall I liked the best, but that's probably just because he was forced to underplay, seeing as his character was an android.

Ebert quotes Lumet's book on filmmaking as to the techniques he used to increase the claustrophobia and tension as the film goes on (camera moves from above to eye level to below through the film; lens changes shrink the perceived space). That's cool, I guess. Contrivances like that would be more effective if the script wasn't already so tightly schematic. I feel the claustrophobia and suffocation not from the closeness of the space, or the heat of the simulated day, but from the airlessness of the screenplay. It's so tightly controlled, all in the service of its hit-you-over-the-head message that there's no room to breathe. No spontaneity, no reality. The film has a lesson it wants me to learn and it won't let me leave until my brain's been pounded to mush.

That even might be OK if it was an interesting lesson. But no, the message is "Jury trials are swell! See how great humans can be when they get together and talk! All we need to do to defeat evil and prejudice and hatred is talk it out, man!" Not only is that wrong, it isn't even particularly close to true. Well, juries are swell, that's true. Yay America! For adopting a legal custom dating back thousands of years and codified in the English-speaking world for 800 years! USA! The rest is a liberal pipe dream that only works in the scenario because it stacks the deck so egregiously by making evil ugly, stupid and incompetent.

62. The Brothers Rico -

63. The Pajama Game - Doris Day becomes a union leader at a pajama factory and attracts the eye of the company's superintendent John Raitt (looking like Rene Auberjonois as a Lifetime movie villain). Their romance complicates union negotiations, as the uppity Miss Day won't know her place as a proper 1950s housewife. Until she does when Raitt proves the company had been ripping off the workers even more than was previously thought. The workers get their little raise, Day goes home to raise Raitt's kids and everyone lives happily ever after. The plot manages to combine the glories of capitalist patriarchy with all the excitement of union negotiations. Ah, but there's music. A couple of pretty great numbers, choreographed by the man who can do no wrong, Bob Fosse. The standout is Broadway actress Carol Haney (she danced with Fosse in a memorable number at the end of

Kiss Me Kate) and her two big numbers here, "Steam Heat" and "Hernando's Hideaway", which ends up somewhere between the finale from

The Gang's All Here and the "Bohemian Rhapsody" video, are exceptional. In general though, this was a big disappointment coming from director Stanley Donen. I'm going to blame his co-director George Abbott.

64. Until They Sail - A Robert Wise-directed adaptation of a James Michener story. Apparently it isn't based on a Michener novel, which surprises me because the film feels like an adaptation of a superlong epic, where the screenwriters have taken out all the small moments of character and location development and simply included every big dramatic moment from the book. The film starts at level-nine melodrama, as one of four sisters in WW2 era New Zealand screams her way out of the house to fulfill her lifelong dream of being a sexual plaything for lonely soldiers and hardly tones down for more than five minutes at a time from there on as the various other sisters get romantically involved, or not, with various other servicemen. There are a lot of great actors doing the best they can, especially Paul Newman, Jean Simmons and Joan Fontaine. Though I'm still pondering how Fontaine, 40 at the time of the film's release (but looking great, of course), got cast as the sister of 15 year old Sandra Dee. Must be some family.

65. Ducking the Devil -

66. A Face in the Crowd - Patricia Neal almost makes this work, she's got the craziest eyes since Ida Lupino in her prime. But the rest is a big loud mess of a scattershot satire that doesn't make a whole lot of sense. It's a parody of populism, but aside from Griffith's overplayed folksiness, there's no reason to believe he would ever be popular It's just asserted, along with his inevitable corruption. He goes from sticking it to the man to selling out to a New York ad agency in the blink of an eye, with no explanation. All that's fine as far as it goes, satire doesn't demand characterization or believable motivations, but it should at least have something interesting to say. This film breaks the exciting news that elites pose as and co-opt populists to further their ends, but the film shies away from almost any kind of real political statement (there's one minor mention of wanting to get rid of Social Security). In the end, we're left with the love triangle from

Broadcast News (Neal and Matthau are great together), except that film had real people acting like real people and still managed to say something insightful about the media and politics. It's not the lunatic demagoguery of the Andy Griffiths that does us in, it's the quiet mediocrity of the William Hurts.

67. NY, NY -

68. Birds Anonymous -

69. Designing Woman - Rewatched this Vincente Minnelli romantic comedy with Lauren Bacall and Gregory Peck as mismatched newlyweds recently and it really seemed more like Frank Tashlin than Minnelli to me. The cartoonish effects were fun, especially in the beginning with Peck's hangover emphasized by extra-loud sound effects and a flash of psychedelic imagery, but in the end it just wore on me and felt wrong. Maybe it's the combination of the material and Minnelli, maybe it's the combination of the leads and the material (neither Peck or Bacall are my ideal of screwball leads) or maybe it was the fidgety baby that dragged the last 45 minutes out for two and a half hours, but this is one of my least favorite Minnellis.

70. Jailhouse Rock - Elvis goes to jail for protecting an abused woman, becomes a music sensation and gets ripped off by his buddy. He's Elvis and that's great. So are the songs. The movie's nothing special though.

71. The Three Faces of Eve - Hard to take as seriously as it wants to be taken, unfortunately, because the apparent actuality of multiple personality disorder is swamped by fakery and misdiagnoses and the disproportionate ubiquity of the condition in popular culture. The film begs to be taken literally, it's based on an actual case and tells you so right at the outset, and follows a semi-documentary style tracing the discovery and treatment of a housewife multiple personalities. Perhaps simplified for adaptation (I don't know the real details of the case) Eve's issues appear largely congruent with the repressed state of the American housewife in the 50s (her alternate personality is liberated, independent and sexually aggressive), but the film shies away from any kind of exploration of the case's metaphorical implications in favor of the specificity of a case study. The childhood trauma that apparently caused her disassociation is disappointingly mild. Joanne Woodward is pretty good in the lead role, but Lee J. Cobb just does Lee J. Cobb things as her doctor.

72. Tom's Photo Finish -

73. Zero Hour! - The film

Airplane! got its plot and much of its dialogue from. It's almost as funny. For some reason, Dana Andrews, Linda Darnell and Sterling Hayden, accomplished actors all, star. It must have been tough making ends meet for a decent actor in the late 50s. Hayden's the best, playing the Robert Stack role, his performance is like a dry run for his awesomeness in

Dr. Strangelove. The strangest thing about the film might be that it's set in Canada, on a flight from Winnipeg to Vancouver (the story was originally a CBC television play. Elroy "Crazylegs" Hirsch, a hall of Fame wide receiver plays the pilot, looking like a more rectangular Kirk Douglas. There's an in-joke about this in the film, as one of the passengers (on his way to a big football game) talks about how the Argos have come up with a new position, the flanker, that was actually the position Hirsch pioneered. Anyway, Bosley Crowther

loved it.

74. Pal Joey - Frank Sinatra stars in this film as a wanna-be club owner torn between the rich and vicious Rita Hayworth and the poor and honest Kim Novak. The great Rodgers & Hart soundtrack elevates it quite a bit.

75. The Man of 1000 Faces - Boilerplate biopic that only comes alive when James Cagney, a great actor playing another great actor, recreates Lon Chaney's routines both for film and the vaudeville stage. Cagney was more than a decade older when he made this film than Chaney was when he died, so there's a level of absurdity to the film right from the beginning, but you can imagine why Cagney would want to play the part. Not for the generally unbelievable melodrama surrounding Chaney and his wife (poor Dorothy Malone, this might be her least redeemable character ever?) and their son. Nor for anything particularly interesting in Chaney's character: it remains largely unexplored, though there should be dimensions there; Cagney and director Joseph Pevney (director of some of the best

Star Trek episodes) hint at it at times particularly his unreasonability and a bit of a cruel streak). No, it had to be for those performance scenes, giving Cagney a chance to do some vaudeville, some mime, some crazy physical contortions and what not. The craziest bit of serendipity though: the genius producer of the 1920s Irving Thalberg (the man most responsible for the creation of the studio system) is played by a young Robert Evans, who would go on to be the genius producer of the 1970s (after the collapse of that same studio system). Thinking about Cagney: how many other iconic movie stars play lesser icons in biopics? This happened a lot in the studio era (James Stewart as Glenn Miller, Cary Grant as Cole Porter, etc), but does it ever happen now?

76. 20 Million Miles to Earth - Cheesy B monster movie with great special effects and nothing else to recommend it. An American spaceship crash-lands off the coast of Sicily after traveling to Venus. Child unwittingly rescues monster egg from the ship. It grows rapidly and destroys much of Rome. There's a fantastic fight scene between the monster and an elephant.

77. Sayonara - Costume melodrama of the most mediocre variety about a group of American servicemen who fall in love with Japanese women during the Korean War. Notable as the film with the first Oscar-winning performance by an Asian actor (Myoshi Umecki as Red Buttons's girl), but that's about it. The cast also includes Marlon Brando, Ricardo Montalbon and James Garner. Adapted from a James Michener novel and directed by Joshua Logan, the man responsible for the Eastwood/Marvin musical classic

Paint Your Wagon.

78. The Buster Keaton Story - There is almost nothing in this biopic that has any basis in fact, historical or otherwise. A couple of the film titles are correct (The Balloonatic, The General, College and The Boat are referenced) others are completely made-up. The longest bit of Keaton recreation comes in a fake film called The Criminal that has elements of Cops, The Goat and Sherlock Jr. Donald O'Connor, playing Keaton, does OK with the physical comedy, though he overplays everything (despite the fact that the "Keaton" character is remarked to have a "dead pan", O'Connor mugs as usual for him). When it comes to the facts of Keaton's life, the film gets two things right: he did grow up in vaudeville and he did have a drinking problem. Everything else appears to be a product of writer-director Sidney Sheldon's imagination (including the timing of and causes for Keaton's alcoholism).

The most egregious of the film's many transgressions is the way it paints Keaton's relations with his studios. In the film, Keaton shows up at a studio and talks his way into a contract in which he will star and direct his own films after appearing in a small role in one film (and despite the best efforts of an obstinate director played by Peter Lorre, of all people). He then happily works at that studio ("Famous Studio", seriously it is called that) for years, making hit after hit with his silent films, only to be unable to transition to sound (because of an inability to say his lines properly) which exacerbates his drinking problem to the point that he's no longer able to function. Through all this, his wife (played by Ann Blyth) loyally and understandingly stands by him, until she doesn't. In the end, Keaton triumphantly returns to vaudeville where he finds happiness reenacting his old routines and making people laugh.

In reality, Keaton worked for quite awhile before getting a starring role, most prominently as a sidekick for Fatty Arbuckle, one of the biggest stars of the era. It was only after the scandal that killed Arbuckle's career that Keaton became a star in his own right, and even then he only occasionally was his own director, more often working in collaboration with Edward Cline or someone else. During the silent era, he didn't work for a studio, rather he worked with independent producer Joseph Schenk. It was at the end of this era, when sound came in, that Keaton signed with MGM (after the financial disaster of The General), where he made his last silents and several talkies. Far from being unable to transition, Keaton's talkies were immensely successful commercially, though fairly weak artistically, mostly because the studio system limited his creative input as much as possible and refused to let him even co-direct. (I reviewed all the late Keaton films here).

Keaton was an alcoholic, and his problem became increasingly worse during the MGM years. But all accounts I've seen place the blame for that on his awful marriage (his second) to Mae Scriven (1933-36). Both of these marriages are unmentioned in the film, though the marriage that is in the film seems roughly comparable to his third and final one (to Eleanor Norris) from 1940 until his death in 1966, that he credited with helping him kick alcohol and restart his career. A career which far from being confined to the vaudeville stage, had him steadily working in film and television for 25 years.

But does any of this matter? Does a film, even a biographical picture, have to be bound by the basic facts of history? Shouldn't it be allowed to tell its own story in its own way, as long as that story is itself, entertainingly told? I do think there's a limit beyond which the truth can be stretched too far in the name of art. Despite our best efforts to ignore, obfuscate, reframe, mythologize and narrativize them, things actually did happen in the past just as they continue to happen in the present and will keep on happening in the future. There really was a Buster Keaton.

79. The Comedian - Over-written, over-directed, over-acted and it's

not even over yet.

15 minutes to go. Over.

It's not necessarily bad, it's just way too much for me. Mickey Rooney is pretty great. But all the yelling. So much yelling. I can't take the yelling.

80. Old Yeller - The classic Disney film of a boy and his dog notable mainly for scarring millions of children with its sappy act of doggy euthanasia. It seems like there was a lot more death in the Disney movies of the mid-20th century than they'd allow now, but I'd have to watch some of the "family" films out today to know for sure, and that is not going to happen.

.jpg)

_-_movie_poster.jpg)