These are the 2000 Endy Awards, wherein I pretend to give out maneki-neko statues to the best in that year in film. Awards for many other years can be found in the Endy Awards Index. Eligibility is determined by imdb date and by whether or not I've seen the movie in question. Nominees are listed in alphabetical order and the winners are bolded. And the Endy goes to. . .

Best Picture:

1. La Commune (Paris 1871)

2. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

3. In the Mood for Love

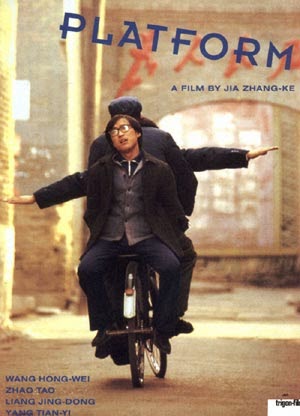

4. Platform

5. Yi yi

So in a year with four of the most-acclaimed Chinese-language films of all-time (the two that appear on Sight & Sound-type lists, the one that is the only Chinese film to ever get any real Oscar consideration and a favorite among the critical intelligentsia), I'm going with a four hour documentary about a leftist revolt in 19th Century France. I'm unpredictable.

2. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

3. In the Mood for Love

4. Platform

5. Yi yi

So in a year with four of the most-acclaimed Chinese-language films of all-time (the two that appear on Sight & Sound-type lists, the one that is the only Chinese film to ever get any real Oscar consideration and a favorite among the critical intelligentsia), I'm going with a four hour documentary about a leftist revolt in 19th Century France. I'm unpredictable.

Best Director:

1. Peter Watkins, La Commune (Paris 1871)

2. Ang Lee, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

3. Wong Kar-wai, In the Mood For Love

4. Platform, Jia Zhangke

5. Yi yi, Edward Yang

With Crouching Tiger's American popularity came the inevitable backlash from the genre fan corner, with the film's various Miramaxisms providing easy fodder (why Anglicize one character name? Why? And yes, it wasn't Miramax who released it, but Sony, still the flattening aesthetic remains the same). But getting beyond all that, the film remains remarkably accomplished, setting a new standard for prestige martial arts films, one to which every subsequent film this century has aspired. Credit for that has to go to Lee (though I'd like to give a special Endy to Yuen Woo-ping for his choreography and action direction as well).

2. Ang Lee, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

3. Wong Kar-wai, In the Mood For Love

4. Platform, Jia Zhangke

5. Yi yi, Edward Yang

With Crouching Tiger's American popularity came the inevitable backlash from the genre fan corner, with the film's various Miramaxisms providing easy fodder (why Anglicize one character name? Why? And yes, it wasn't Miramax who released it, but Sony, still the flattening aesthetic remains the same). But getting beyond all that, the film remains remarkably accomplished, setting a new standard for prestige martial arts films, one to which every subsequent film this century has aspired. Credit for that has to go to Lee (though I'd like to give a special Endy to Yuen Woo-ping for his choreography and action direction as well).

Best Actor:

1. Chow Yun-fat, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

2. Jiang Wen, Devils on the Doorstep

3. Tony Leung, In the Mood for Love

4. Michael Douglas, Wonder Boys

5. Wu Nien-jen, Yi yi

This is Tony Leung's first Endy win. But I suspect it won't be his last.

2. Jiang Wen, Devils on the Doorstep

3. Tony Leung, In the Mood for Love

4. Michael Douglas, Wonder Boys

5. Wu Nien-jen, Yi yi

This is Tony Leung's first Endy win. But I suspect it won't be his last.

Best Actress:

1. Michelle Yeoh, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

2. Björk, Dancer in the Dark

3. Gillian Anderson, House of Mirth

4. Maggie Cheung, In the Mood for Love

5. Lee Eunju, Virgin Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors

Björk is so good she almost makes me like that movie. All these other actresses are amazing as well. Very strong group this year.

2. Björk, Dancer in the Dark

3. Gillian Anderson, House of Mirth

4. Maggie Cheung, In the Mood for Love

5. Lee Eunju, Virgin Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors

Björk is so good she almost makes me like that movie. All these other actresses are amazing as well. Very strong group this year.

Supporting Actor:

1. Philip Seymour Hoffman, Almost Famous

2. Jack Black, High Fidelity

3. Benicio del Toro, Traffic

4. Robert Downey Jr, Wonder Boys

5. Issei Ogata, Yi yi

2. Jack Black, High Fidelity

3. Benicio del Toro, Traffic

4. Robert Downey Jr, Wonder Boys

5. Issei Ogata, Yi yi

Supporting Actress:

1. Parker Posey, Best in Show

2. Zhang Ziyi, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

3. Cheng Pei-pei, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

4. Thandie Newton, Mission: Impossible 2

5. Holly Hunter, O Brother Where Art Thou?

I'm following the Oscar convention of categorizing Zhang as Supporting, but isn't she really the lead? Anyway, this way I can nominate for folks in the lead category this year, when it's much richer than the supporting group. Zhang will win Best Actress in 2004 and just miss winning it again in 2013.

2. Zhang Ziyi, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

3. Cheng Pei-pei, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

4. Thandie Newton, Mission: Impossible 2

5. Holly Hunter, O Brother Where Art Thou?

I'm following the Oscar convention of categorizing Zhang as Supporting, but isn't she really the lead? Anyway, this way I can nominate for folks in the lead category this year, when it's much richer than the supporting group. Zhang will win Best Actress in 2004 and just miss winning it again in 2013.

Original Screenplay:

1. Peter Watkins & Agathe Bluysen, La Commune (Paris 1871)

2. Wong Kar-wai, In the Mood for Love

3. Jia Zhangke, Platform

4. Hong Sangsoo, Virgin Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors

5. Edward Yang, Yi yi

This is Hong Sangsoo's sixth Original Screenplay nomination. He'll be nominated five times in six years from 2008-2013, winning in 2010.

2. Wong Kar-wai, In the Mood for Love

3. Jia Zhangke, Platform

4. Hong Sangsoo, Virgin Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors

5. Edward Yang, Yi yi

This is Hong Sangsoo's sixth Original Screenplay nomination. He'll be nominated five times in six years from 2008-2013, winning in 2010.

Adapted Screenplay:

1. James Schamus, Wang Hui-Ling & Tsai Kuo-Jung, Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon

2. Jiang Wen, Shi Ping, Shi Jianquan & You Fengwei, Devils on the Doorstep

3. Terence Davies, House of Mirth

4. Joel & Ethan Coen, O Brother Where Art Thou?

5. Steve Kloves, Wonder Boys

Top to bottom, this is the strongest Adapted Screenplay group since 2009.

2. Jiang Wen, Shi Ping, Shi Jianquan & You Fengwei, Devils on the Doorstep

3. Terence Davies, House of Mirth

4. Joel & Ethan Coen, O Brother Where Art Thou?

5. Steve Kloves, Wonder Boys

Top to bottom, this is the strongest Adapted Screenplay group since 2009.

Non-English Language Film:

1. La Commune (Paris 1871) (Peter Watkins)

2. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (Ang Lee)

3. In the Mood for Love (Wong Kar-wai)

4. Platform (Jia Zhangke)

5. Yi yi (Edward Yang)

This is the first time in Endy history that this category is identical to the Best Picture category, meaning no English language film got a Picture nomination. In fact, House of Mirth and O Brother, Where Art Thou? only barely sneak into my Top 10 for the year.

2. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (Ang Lee)

3. In the Mood for Love (Wong Kar-wai)

4. Platform (Jia Zhangke)

5. Yi yi (Edward Yang)

This is the first time in Endy history that this category is identical to the Best Picture category, meaning no English language film got a Picture nomination. In fact, House of Mirth and O Brother, Where Art Thou? only barely sneak into my Top 10 for the year.

Documentary Film:

1. La Commune (Paris 1871) (Peter Watkins)

2. Jeff Buckley: Live in Chicago

Animated Film:

1. Chicken Run (Nick Park & Peter Lord)

2. Escaflowne: The Movie (Kazuki Akane)

Short Film:

1. The Heart of the World (Guy Maddin)

2. Escaflowne: The Movie (Kazuki Akane)

Short Film:

1. The Heart of the World (Guy Maddin)

Unseen Film:

1. Eureka (Shinji Aoyama)

2. JSA: Joint Security Area (Park Chanwook)

3. Requiem for a Dream (Darren Aronofsky)

4. Werckmeister Harmonies (Béla Tarr & Ágnes Hranitzky)

5. The Yards (James Gray)

Also receiving votes: Suzhou River (Lou Ye), Sexy Beast (Jonathan Glazer), The Vertical Ray of the Sun (Anh Hung Tran), and Barking Dogs Never Bite (Bong Joonho).

2. JSA: Joint Security Area (Park Chanwook)

3. Requiem for a Dream (Darren Aronofsky)

4. Werckmeister Harmonies (Béla Tarr & Ágnes Hranitzky)

5. The Yards (James Gray)

Also receiving votes: Suzhou River (Lou Ye), Sexy Beast (Jonathan Glazer), The Vertical Ray of the Sun (Anh Hung Tran), and Barking Dogs Never Bite (Bong Joonho).

1. La Commune (Paris 1871)

2. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

3. The Heart of the World

4. In the Mood for Love

5. Tears of the Black Tiger

2. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

3. The Heart of the World

4. In the Mood for Love

5. Tears of the Black Tiger

Cinematography:

1. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

2. The Heart of the World

3. In the Mood for Love

4. Tears of the Black Tiger

5. Yi yi

2. The Heart of the World

3. In the Mood for Love

4. Tears of the Black Tiger

5. Yi yi

Art Direction:

1. La Commune (Paris 1871)

2. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

3. The Heart of the World

4. Songs from the Second Floor

5. Tears of the Black Tiger

A revolution in a soundstage cavern.

2. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

3. The Heart of the World

4. Songs from the Second Floor

5. Tears of the Black Tiger

A revolution in a soundstage cavern.

Costume Design:

1. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

2. In the Mood for Love

3. O Brother, Where Art Thou?

4. Platform

5. Tears of the Black Tiger

Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung's outfits create at least 75% of the romance in their film.

2. In the Mood for Love

3. O Brother, Where Art Thou?

4. Platform

5. Tears of the Black Tiger

Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung's outfits create at least 75% of the romance in their film.

Make-up:

1. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

2. Help!!!

3. O Brother, Where Art Thou?

4. Tears of the Black Tiger

5. X-Men

2. Help!!!

3. O Brother, Where Art Thou?

4. Tears of the Black Tiger

5. X-Men

Original Score:

1. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

2. Dancer in the Dark

3. The Heart of the World

4. Needing You. . .

5. Time and Tide

Tough call here, but while I love Björk, Tan Dun is absolutely essential to Crouching Tiger. Possibly the best integration of music into a martial arts film ever.

2. Dancer in the Dark

3. The Heart of the World

4. Needing You. . .

5. Time and Tide

Tough call here, but while I love Björk, Tan Dun is absolutely essential to Crouching Tiger. Possibly the best integration of music into a martial arts film ever.

Adapted Score:

1. High Fidelity

2. In the Mood for Love

3. O Brother Where Art Thou?

4. Platform

5. Tears of the Black Tiger

Original Song:

1. "In the Musicals", Björk, Dancer in the Dark

2. "I've Seen It All", Björk, Dancer in the Dark

3. "Gan Qing Xian Sang", Sammi Cheng, Needing You. . .

4. "Things Have Changed", Bob Dylan, Wonder Boys

Bob Dylan won the Oscar this year, which is great because Yay Bob! But much better than his song was his performance of it on the award show, remote from Australia, he kept sidling up to the camera for an extreme close-up of his Cesar Romero mustache. It was hilarious.

2. In the Mood for Love

3. O Brother Where Art Thou?

4. Platform

5. Tears of the Black Tiger

Original Song:

1. "In the Musicals", Björk, Dancer in the Dark

2. "I've Seen It All", Björk, Dancer in the Dark

3. "Gan Qing Xian Sang", Sammi Cheng, Needing You. . .

4. "Things Have Changed", Bob Dylan, Wonder Boys

Bob Dylan won the Oscar this year, which is great because Yay Bob! But much better than his song was his performance of it on the award show, remote from Australia, he kept sidling up to the camera for an extreme close-up of his Cesar Romero mustache. It was hilarious.

Sound:

1. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

2. In the Mood for Love

3. Platform

4. Tears of the Black Tiger

5. Yi yi

2. In the Mood for Love

3. Platform

4. Tears of the Black Tiger

5. Yi yi

Sound Editing:

1. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

2. Gladiator

3. Mission: Impossible 2

4. The Perfect Storm

5. Tears of the Black Tiger

2. Gladiator

3. Mission: Impossible 2

4. The Perfect Storm

5. Tears of the Black Tiger

Visual Effects: