As we as a nation prepare to execute millions of large flightless birds in honor of our gods, some thoughts on a few recently seen movies.

As we as a nation prepare to execute millions of large flightless birds in honor of our gods, some thoughts on a few recently seen movies.Three Times - The latest Hou Hsiao-hsien is three love stories set in three different time periods with the same two actors in each story (Shu Qi, from Millenium Mambo and Chang Chen from Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon). The first, concerning a soldier looking for the girl he loves, a pool hall attendant, is set in 1966 and the mood and quirky humor of the story is reminiscent of Wong Kar-wai's trilogy of period films (Days Of Being Wild especially). The second section, set in 1911, concerns a young revolutionary and the prostitute who loves him and hopes to marry him. The whole section is in the style of a silent movie, complete with intertitles, but shot in a vivid color, dominated by purple, brown and gray. The third sequence is set in the present, with the man as a photographer, in love with a singer despite the both of them having girlfriends of their own. Like all Hou films, it's beautiful, with long, floating takes from a fixed point of view (the camera pans but does not swirl or track). It's a small film with an epic's worth of meanings: the changing definitions and codes and styles of love, the transformations in the way men and women relate to each other, the history of Taiwan over the last 100 years, both politically and culturally, and most interestingly (to me) how in the 21st century the past is just another aspect of the present. In the future the past will be ever present. The #2 film of 2005, behind only The New World.

A Night To Remember - This 1958 telling of the story of the sinking of the Titanic was amply ripped off in The Biggest Movie Ever. It manages to avoid all the bad parts about James Cameron's epic (the generic love story, Paxton and Zane), while telling the always moving, if exceedingly familiar story. Director Roy Ward Baker (who?) shoots in a stark, realistic black and white style that, combined with the relatively non-existent histrionics makes this the stereotypically stiff-upper lipped British reaction to disaster, right down to the ending noting the socially beneficial responses to the tragedy. The #5 film of 1958.

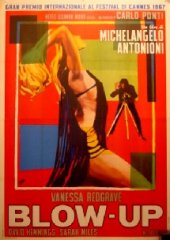

Blowup - Michelangelo Antonioni's Swinging London mystery about a photographer who thinks he may have accidentally captured a murder on film while shooting in a park one afternoon. He tries to investigate the crime, but keeps getting distracted by the temptations of life in the mid-60s: hot clubs, sex with multiple wanna-be models, Vanessa Redgrave, the need to buy a giant wooden propeller, mimes, and so on. David Hemmings plays the photographer with the same blank, bored cool that one would expect in a film by the director of L'Aventura, the classic icy ode to ennui. I enjoyed this film a lot more than that one, the ideas are the same, but Blowup is more playful. The #4 film of 1966.

Blowup - Michelangelo Antonioni's Swinging London mystery about a photographer who thinks he may have accidentally captured a murder on film while shooting in a park one afternoon. He tries to investigate the crime, but keeps getting distracted by the temptations of life in the mid-60s: hot clubs, sex with multiple wanna-be models, Vanessa Redgrave, the need to buy a giant wooden propeller, mimes, and so on. David Hemmings plays the photographer with the same blank, bored cool that one would expect in a film by the director of L'Aventura, the classic icy ode to ennui. I enjoyed this film a lot more than that one, the ideas are the same, but Blowup is more playful. The #4 film of 1966.The Tao Of Steve - Entertaining, if typical, Gen X indie comedy about a fat slacker with a quirky philosophy and his adventures in search of true love. Donal Logue is very good as the slacker, and the setting (Santa Fe, New Mexico) is new and interesting, and there are some clever lines, but the supporting performances are below par, even for an indie. A slight, but watchable film. The #21 movie of 2000.

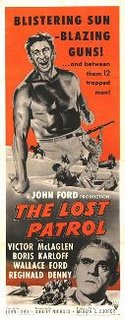

The Lost Patrol - Another in the John Ford marathon, this 1934 film stars Victor McLaglen (The Quiet Man, She Wore A Yellow Ribbon) as the leader of a troop of British soldiers in Mesopotamia, surrounded at an oasis by unseen Arabs who snipe them off one by one. The unseen nature of the enemy eventually drives the men nuts. The music, by Max Steiner, is more than a little reminiscent of the score he'd write eight years later for Casablanca. There's some nice imagery, a shirtless McLaglan mowing down a line of Arabs with a machine gun seems right out of Rambo III, and some good supporting performances (including a histrionic Boris Karloff). An entertaining enough little film, barely over an hour long, but it doesn't really compare to Ford's greatest films (unfair, I know).

The Lost Patrol - Another in the John Ford marathon, this 1934 film stars Victor McLaglen (The Quiet Man, She Wore A Yellow Ribbon) as the leader of a troop of British soldiers in Mesopotamia, surrounded at an oasis by unseen Arabs who snipe them off one by one. The unseen nature of the enemy eventually drives the men nuts. The music, by Max Steiner, is more than a little reminiscent of the score he'd write eight years later for Casablanca. There's some nice imagery, a shirtless McLaglan mowing down a line of Arabs with a machine gun seems right out of Rambo III, and some good supporting performances (including a histrionic Boris Karloff). An entertaining enough little film, barely over an hour long, but it doesn't really compare to Ford's greatest films (unfair, I know).The Hurricane - Part of the six movie John Ford marathon on TCM yesterday, five I've which I hadn't seen and tivo'd. It's hurt by weak, ethnically inappropriate, and mediocre, lead actors (Jon Hall and Dorthy Lamour), but gets fine supporting performances from Thomas Mitchell and Raymond Massey. Massey plays the French colonial administrator of a small South Seas Island who unbendingly enforces the law against an unjustly convicted native (a hero to his people, played by Jon Hall). After repeated attmpts at escaoe from prison, Hall finally makes his way home, only to see the entire island wiped away by a massive hurricane. The special effects in the final sequence are amazing for any time, but especially for 1937. There are even echoes of themes Ford would develop fully in The Searchers (and certainly the mileu is something he'd return to in his late light classic Donovan's Reef). Mary Astor (from The Maltese Falcon) is largely wasted in a supporting role as Massey's wife.

Marie Antoinette - Some notes on the most controversial film of the year so far:

Marie Antoinette - Some notes on the most controversial film of the year so far:I thought Kirsten Dunst was very good, but I've a weakness for her. Steve Coogan, Danny Huston and Judy Davis are largely wasted. I liked Jason Schwartzman a lot. His Louis XVI is benign, incompetent and amiably clueless and surprisingly understated for Schwartzman, who's usually pretty broad.

Cinematographically, it was pretty but not all that interesting. I think the film is really overrated visually. It has a lot in common with the similarly overrated Memoirs Of A Geisha. Both films are full of shots of beautiful things shot in a not particularly interesting or innovative style. The costume design was great. the set decoration was ridiculously baroque, I'm not sure if it's historically accurate or over-the-top or both.

I thought the parallels in the film between the fads Marie Antoinette takes up and contemporary fads of upper class women were potentially very clever (the sequence in Petit Trianon with the herbs and the lambs was hilarious), but I'm unsure if Coppola's aware of that irony. I'm not sure if the film is satire or tragedy, but I don't think it can be both.

I liked the improvisational vignette style through the first two-thirds of the film, but as the events of the film became more serious, I found the lack of historical context really annoying. There's no explanation for why the French people turn against her. We just experience it as a series of seemingly random horrible things happening to her. I don't believe that Marie Antoinette was as ignorant of the larger context of her life and society as this film is. The fact that we have glimpses (only glimpses) of her larger awareness confounds me. If the point is to show a girl adrift in a world she doesn't understand, why create scenes where she understands her world perfectly? Radically divorced from social context, the film is not about Marie Antoinette, but about Sofia Coppola. And I really don't care how difficult Sofia Coppola thinks her life of privilege is. Try as I might, I really don't think there's anything to this film other than "aww, look at the poor little rich girl." At least she's cute, I guess.

I liked the improvisational vignette style through the first two-thirds of the film, but as the events of the film became more serious, I found the lack of historical context really annoying. There's no explanation for why the French people turn against her. We just experience it as a series of seemingly random horrible things happening to her. I don't believe that Marie Antoinette was as ignorant of the larger context of her life and society as this film is. The fact that we have glimpses (only glimpses) of her larger awareness confounds me. If the point is to show a girl adrift in a world she doesn't understand, why create scenes where she understands her world perfectly? Radically divorced from social context, the film is not about Marie Antoinette, but about Sofia Coppola. And I really don't care how difficult Sofia Coppola thinks her life of privilege is. Try as I might, I really don't think there's anything to this film other than "aww, look at the poor little rich girl." At least she's cute, I guess.Much like in Lost In Translation, Coppola totally lost it in the last third of the film. She has good taste in the directors she likes to copy (Hou and Wong in particular are obvious stylistic influences), but she has yet to make a truly meaningful statement out of all that style. Without any real meaning, it's all just a pose, it's all fashion.

I still can't shake MARIE and think it's getting a bad rap for all the obvious, wrong reasons. There's a lot more earnest artistic plight in it than Coppola's getting credit for. In a way, it's a piece of criticism on the nature of biopics and as such is pretty illuminating. I think its problems aren't in her attempts to articulate her problems with today's society (her message is rightly clear) but its characterizations near the close. That, and I wanted it to end a lot like FAT GIRL, which may be a perfect film, despite being arduous and ugly. But, as is, the parting shot is, as I said in my reivew, indelible and inspired, offering a new read on her empty life. In place of a beheading we're given her empty palace, the gild falling from the moulding and a faint echo of the past. Is that all history is, really, for us where, as you say, "in the future the past will be ever present": a pretty textbook with tidy, calculated summations? I think the picture offers a wealth of fuzzy logic but there's some truth in there, too--you just gotta root it out. For me, it's the #8 of 2006 so far and I really want to see it again along with LADY IN THE WATER so I can write an essay about their intriguing populist failures.

ReplyDeleteI really wanted to see THREE TIMES before THE FOUNTAIN so I could write a compare'n'contrast review but I guess that'll have to wait.

BLOW UP is tight. ZABRISKIE may be my favorite after CHUNG KUO CINA.

I saw TAO OF STEVE on a whim and really dug it. That was when I was a mere high school senior and it taught me the word "solipsism". Oh how far I've come...

I think you're giving Coppola way too much credit. Much like Michael Haneke, Coppola's films create the aura of meaning by being so totally empty. You can project any meaning you like on a blank enough canvas.

ReplyDeleteHou's films are the opposite of that. Meaning pops out of every corner of the frame, always obliquely. The more I think about his films, the more complex and fascinating they become as possible interpretations and meanings open and reveal themselves. The more I think about Marie Antoinette, the simpler it becomes.

The final shot of Marie Antoinette shows the crumbling of a facade, if I remember correctly. Seems like a pretty obvious metaphor to me.

Hou is fascinated by history and its relation to the present. He made a whole trilogy about Taiwainese history (none of which I've seen yet). Of his four films I've seen, only Millennium Mambo is solely about its moment. Flowers Of Shanghai is a period piece, Café Lumière is a tribute to Ozu, both in style (the camera never moves) and thematically (Ozu's brand of domestic humanism).

Coppola, though, doesn't care about history. She appropriates the story of Marie Antoinette, and attempts to make her sympathetic an tragic to make a point about her own life as a child of privilege in the 21st century. History is alive for Hou, for Coppola it is a dead thing to be appropriated and decontextualized and rearranged as we see fit.

The same mentality allows her to ape the style of Chinese filmmakers for a borderline racist exercise in the wonders of "orientalism" cloaked in a dull and conventional Hollywood romance. (Does Coppola's Lost In Translation = DeMille's The Cheat? A question for further study).

I don't have any problem with anachronism in particular. I love all of Baz Luhrman's films, the last two of which follow the same strategy of applying modern music to a period setting. But with Luhrman the past and the present mingle to create meaning. With Coppola, they combine to choke it off. Luhrman's films are about love, the modernity illuminates Shakespeare and fin de siècle Paris and shows us that the raw emotions in the classical stories don't change over time but are still primally with us. Coppola's films are about the boredom of rich white girls. Her cultural appropriations can't help but be imperialist and oppressive. Her films show a fundamental lack of curiosity about the world around her, past or present.