Friday, November 03, 2006

Wednesday, November 01, 2006

Movie Roundup: All Saints' Day Edition

Trying to catch up on what's been a busy month of movie watching and working. So many movies, so little time to not blog.

Trying to catch up on what's been a busy month of movie watching and working. So many movies, so little time to not blog.The Bank Dick - My first W. C. Fields experience is a happy one with this quite hilarious misanthropic fantasy about an old drunk who accidentally foils a bank robbery and gets a job out of it. Complications ensue when he encourages his prospective son-in-law to embezzle some money in order to invest it on the eve of the bank examiner's inspection. The supporting actors are rather poor, barely above the level of props for Fields's brilliant combination of laziness, solipsism, alcohol and spite. Definitely a subject for further research.

Nothing Sacred - Fredric March and Carole Lombard star in this screwball comedy about a reporter writing a series of stories on a young girl dying from radium poisoning. Turns out the girl isn't dying after all, but just pretending to get a free trip to New York. Girl and reporter fall in love and madcap hilarity ensues. Lombard's terrific, as usual, but March is way too stiff and dull for this genre, lacking the fluidity of Cary Grant or Jimmy Stewart. It's an entertaining enough film, though shot in an early version of Technicolor that looks way too green.

Ball Of Fire - This Howard Hawks screwball comedy stars Gary Cooper as the head of an eccentric group of brainy encyclopedists made up of some of the best character actors of the 30s and 40s. their little world is disrupted when they venture into the streets to further their knowledge of contemporary slang (for an encyclopedia entry) and come home with floozy Barbara Stanwyck. Stanwyck's on the run from the cops who want her to testify against her boyfriend (Dana Andrews, a gangster). Cooper, of course, falls for the girl, apparently the first on of them those guys have seen in decades. It's not as anarchic or brilliant as Hawks's best comedies (Bringing Up Baby, His Girl Friday), but it's a fun film with fine performances all around, especially by Richard Haydn (the guy who was the voice of the caterpillar in Disney's Alice In Wonderland) as one of the wistful old professors. Even Gary Cooper managed to impress me as an actual human being, a first for him.

Smiles Of A Summer Night - This early Ingmar Bergman film is a little overlabeled as a comedy. It is instead a member of the upper-class partner switching genre, who's most illustrious example is Jean Renoir's masterpiece The Rules Of The Game. This film plays as a pale imitation of that one, with less characters the love geometry is less complicated, and the film lacks all the social commentary of the other, with it's intersecting relationships between the various French classes on the eve of World War II and it's complex nostalgia for a more civilized time. Bergman's film, by comparison, is set at the turn of the century almost entirely among the upper class. There is a sequence with a maid and a butler in the final third of the film that to some extent works as a comparison to the more complicated lives of the rich characters, but it feels tacked on and simplistic (if not condescending) relative to Renoir's film.

Smiles Of A Summer Night - This early Ingmar Bergman film is a little overlabeled as a comedy. It is instead a member of the upper-class partner switching genre, who's most illustrious example is Jean Renoir's masterpiece The Rules Of The Game. This film plays as a pale imitation of that one, with less characters the love geometry is less complicated, and the film lacks all the social commentary of the other, with it's intersecting relationships between the various French classes on the eve of World War II and it's complex nostalgia for a more civilized time. Bergman's film, by comparison, is set at the turn of the century almost entirely among the upper class. There is a sequence with a maid and a butler in the final third of the film that to some extent works as a comparison to the more complicated lives of the rich characters, but it feels tacked on and simplistic (if not condescending) relative to Renoir's film.Anyway, aside from not being as good as one of the five greatest films of all-time, this is a fine film, easily the most pleasant and charming Bergman I've seen. the performances are all quite good, though I was surprised not to find Max von Sydow, who i believe is in every other Swedish film I've ever seen.

Imitation Of Life - I've finally seen my first Douglas Sirk film, despite the fact that I managed to write a short paper on this film in college. It's a melodrama of the ungrateful daughter variety, with some very impressive examinations of racism, passing and white liberal hypocrisy. Lana turner plays the mom who wants to be an actress and Juanita Moore plays her maid. The two ladies also have daughters (Saundra Dee plays the grown-up white girl and Susan Kohner the grown-up black girl who wishes she wasn't), and Turner has a love interest, the treelike John Gavin (Psycho, Spartacus). Like all of Sirk's classics, the drama is uber-melo and the acting is heightened to (past?) the point of hysteria and the colors are vibrant and Techni. There's a lot going on with Sirk and I really need to see more of his films and watch them a lot more closely. The number 11 film of 1959, a truly terrific year for film.

Ordet - Another Carl Theodor Dreyer classic, this time revolving around a small farming family (one father, three sons) and their religious squabble with a neighboring family as a son from one family wants to marry the daughter of another. Complicating matters is that one of the other sons is crazy (thinks he's Jesus) and the third has a wonderful wife who faces death while giving birth one night. The film's generally described as "a profound examination of faith and what it means to believe in God" or something, and that's true. But the film succeeds not because of the depth of its philosophy, but because of the realism and convincing drama of its scenario and mise en scène (long shots, slow editing, theatrical, yet convincing performances, especially by the actors who play the crazy son and the father).

Ordet - Another Carl Theodor Dreyer classic, this time revolving around a small farming family (one father, three sons) and their religious squabble with a neighboring family as a son from one family wants to marry the daughter of another. Complicating matters is that one of the other sons is crazy (thinks he's Jesus) and the third has a wonderful wife who faces death while giving birth one night. The film's generally described as "a profound examination of faith and what it means to believe in God" or something, and that's true. But the film succeeds not because of the depth of its philosophy, but because of the realism and convincing drama of its scenario and mise en scène (long shots, slow editing, theatrical, yet convincing performances, especially by the actors who play the crazy son and the father).Bride Of The Monster - Another Ed Wood classic, though it lacks the terrifying autobiography and just plain weirdness of Glen Or Glenda or the let's put on a show comic bravado of Plan 9 From Outer Space. Bela Lugosi plays a mad scientist who creates radioactive monsters and kidnaps a young female journalist (Loretta King) with the help of his professional wrestling henchman Tor Johnson. The acting is terrible, the props as cheap as they come and the story generic as any sci-fi film of the 50s. It's Wood's most successful film in this Hollywood sense, but the least interesting of his work I've seen.

The Old Dark House - Refugees from a driving rainstorm find shelter in a creepy house populated by a demented family in this 1932 James Whale creepfest starring Boris Karloff and Charles Laughton. Even more effectively than in Frankenstein, Whale adapts the shadowy darkness of the silent German Expressionist classics to the early sound era, a time when most Hollywood directors had seemingly forgotten everything that had been learned about the creation of mood, atmosphere and meaning through image over the prior 20 years in the struggle to capture the novelty of actors actually talking (By 1932, this phase of film was thankfully on it's way out, thanks to Whale, Howard Hawks (Scarface) and Busby Berkeley). In this sense, this film is a prototype of the cheap, atmospheric horror films Val Lewton and Jacques Tourneur would make in the 40s (Cat People, The Leopard Man, I Walked With A Zombie), which were all shadows and psychology and without much in the way of violence. This film, though, does end with a lengthy fight scene and conflagration as somebody lets the crazy brother out of his cell in the basement and he terrorizes the women, beats up the men and sets the whole dark house on fire.

The Old Dark House - Refugees from a driving rainstorm find shelter in a creepy house populated by a demented family in this 1932 James Whale creepfest starring Boris Karloff and Charles Laughton. Even more effectively than in Frankenstein, Whale adapts the shadowy darkness of the silent German Expressionist classics to the early sound era, a time when most Hollywood directors had seemingly forgotten everything that had been learned about the creation of mood, atmosphere and meaning through image over the prior 20 years in the struggle to capture the novelty of actors actually talking (By 1932, this phase of film was thankfully on it's way out, thanks to Whale, Howard Hawks (Scarface) and Busby Berkeley). In this sense, this film is a prototype of the cheap, atmospheric horror films Val Lewton and Jacques Tourneur would make in the 40s (Cat People, The Leopard Man, I Walked With A Zombie), which were all shadows and psychology and without much in the way of violence. This film, though, does end with a lengthy fight scene and conflagration as somebody lets the crazy brother out of his cell in the basement and he terrorizes the women, beats up the men and sets the whole dark house on fire.Beyond A Reasonable Doubt - Dana Andrews plays a reporter who conspires with his future father-in-law to frame himself for a murder in order to prove the lunacy of applying the death penalty based on circumstantial evidence. unfortunately for him, but not too surprising, is when the old guy dies, there's no one around to prove his actual innocence. Director Fritz Lang reportedly hated this film, and it shows in the perfunctory job he did directing it. It has none of the aggressive style and outrage of his classic anti-lynching film Fury, to say nothing of the experimentality of his noir classics (M, Metropolis, The Big Heat, etc). This is Lang going through the motions, and it works as a kind of entertainment. Like an episode of Murder, She Wrote. With Joan Fontaine as the unfortunate fiancée.

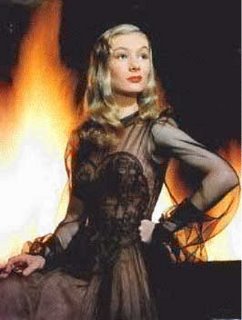

I Married A Witch - French director René Clair is responsible for some classic films which I've never seen (Le Million, À Nous La Liberté), but I have seen this charmingly titled Hollywood film from 1942. The adorable Veronica Lake plays the eponymous bride, who, along with her witch relatives is trapped in a tree in Puritan New England only to be released and unleashed on the family that captured her 300 years later, where, through the unfortunate application of a love spell, she falls in love with the descendent of the man who tormented her originally. The emergence of Lake and her father from their tree prison as wisps of smoke that float across the land and find themselves watching a party of swells from inside beer bottles is lyrical and lovely, while in keeping with the absurd spirit of the film. It's just the best of many fine sequences from Clair, a director who I'll now have to seek out more from (ah, the ever-expanding queue). Lake is wonderful as the witch, and not just because she wears a succession of quite clingy dresses. She has the ethereality necessary for playing a wisp of smoke, and the comic ability to pull off the screwballity of the comedy. Fredric March, on the other hand, is just as stiff as he was in Nothing Sacred five years earlier.

I Married A Witch - French director René Clair is responsible for some classic films which I've never seen (Le Million, À Nous La Liberté), but I have seen this charmingly titled Hollywood film from 1942. The adorable Veronica Lake plays the eponymous bride, who, along with her witch relatives is trapped in a tree in Puritan New England only to be released and unleashed on the family that captured her 300 years later, where, through the unfortunate application of a love spell, she falls in love with the descendent of the man who tormented her originally. The emergence of Lake and her father from their tree prison as wisps of smoke that float across the land and find themselves watching a party of swells from inside beer bottles is lyrical and lovely, while in keeping with the absurd spirit of the film. It's just the best of many fine sequences from Clair, a director who I'll now have to seek out more from (ah, the ever-expanding queue). Lake is wonderful as the witch, and not just because she wears a succession of quite clingy dresses. She has the ethereality necessary for playing a wisp of smoke, and the comic ability to pull off the screwballity of the comedy. Fredric March, on the other hand, is just as stiff as he was in Nothing Sacred five years earlier.